Do Dream Jobs Even Exist Anymore?

careerism, creativity and apple tv's 'the studio'

Television is rich with narratives that interrogate the border between passion and capitalism, our dreams and our work: Industry showcases the erosion of young financial analysts in pursuit of capital gain and success; Hacks illustrates how you can reach the top of your creative field, and still be miserable; and Severance speculates a future where the ills of the workplace have become too much for the off-work psyche, where work-life balance is blue pilled and members of society split their conscious into two parts — those that work and those that play. Our relationship to work is the cultural dilemma of our generation, especially as we think about careerism in proximity to “the dream job.” The project of optimizing the two is on full display in Apple TV’s new comedy, The Studio.

The Studio opens with a Faustian bargain: a newly appointed film executive at Continental Studios (a tongue-in-cheek nod to Universal Studios) must choose between funding the commercially cringe Kool-Aid Man movie (based on the ‘beloved’ American intellectual property, à la Gerwig’s Barbie), or diverting funds to more artistic but less profitable projects like a new Martin Scorsese film.

Matt Remick, perennially frantic and portrayed by the show’s creator and director Seth Rogen, has finally stepped into his dream job. As studio head, he gets to decide which films are greenlit for production and wield decision rights across director selection, marketing, and the final cut. It is quickly established that Remick is an admirer of ‘real films.' You know the kind I’m talking about; the moving pictures that Scorsese loves and not the Marvel ones he hates. And yet, in this new role, pitched to greater importance than the creative oversight and validation he seeks is his primary responsibility: to make the studio money. The double bind of creative capitalism is established through the gorilla grip of golden handcuffs, shackling Remick to Continental’s prioritization of financial results over evocative, life-changing cinema. Throughout the comedy, we watch as Remick explores the question of our generation: Can great art exist under capitalism?

But this essay is not about that. In fact, I believe The Studio, already four episodes in, has shown its hand. From the scenes that contain elements of film production, it’s clear that none of the movies that leave the Continental soundstage are excellent or even good. The Studio wants you to know that capitalism has diseased well-intentioned art and, specifically, pillaged cinema. For as buoyant and witted the show is in tone, composed of backhanded quips that land with a Succession-like punch, The Studio’s outlook on the future of the creative industry is bleak, establishing a wince of nihilism through its high farce plot.

What I love most about The Studio is its blend of reality and fiction and its decision to cast real Hollywood contributors — Charlize Theron, Paul Dano, Greta Lee, Anthony Mackie, Zac Efron, Olivia Wilde — to play elevated versions of themselves. In a strange way, this fantastical expression of the self points towards the truth. Like the fluttering white dress of Marilyn Monroe over the subway grate, the performance reveals as much as it entertains. When Greta Lee as Greta Lee complains that she had to fly economy for Past Lives promotion, you get the sense that she’s finally able to voice something that she could never in real life, freed through the mouth of her characterized self. In The Studio, she’s willing to accept a bad note from a producer for a better-funded press tour — her own Faustian bargain. When we see Paul Dano, an extremely competent actor in real life, act poorly in one of the nonsense scripts Remick has approved for production, or Ron Howard, the director of the Academy Award-winning A Beautiful Mind, display bad instincts pertaining to the final edit of a new film, we get a window into the wreckage that can arise when an art form is turned into a for profit industry. The creative instincts that spawn from Continental are misguided, which may be true for most art making. Even the great. But for Remick, whose ‘dream job’ it is to see the films for their entirety, out of the weeds and across all its elements as a paying AMC Stubs member eventually would, instead of making decisions based on taste, his opinion is jeopardized by the fact that he’s turned his love of cinema into a job. Capital comes before creativity.

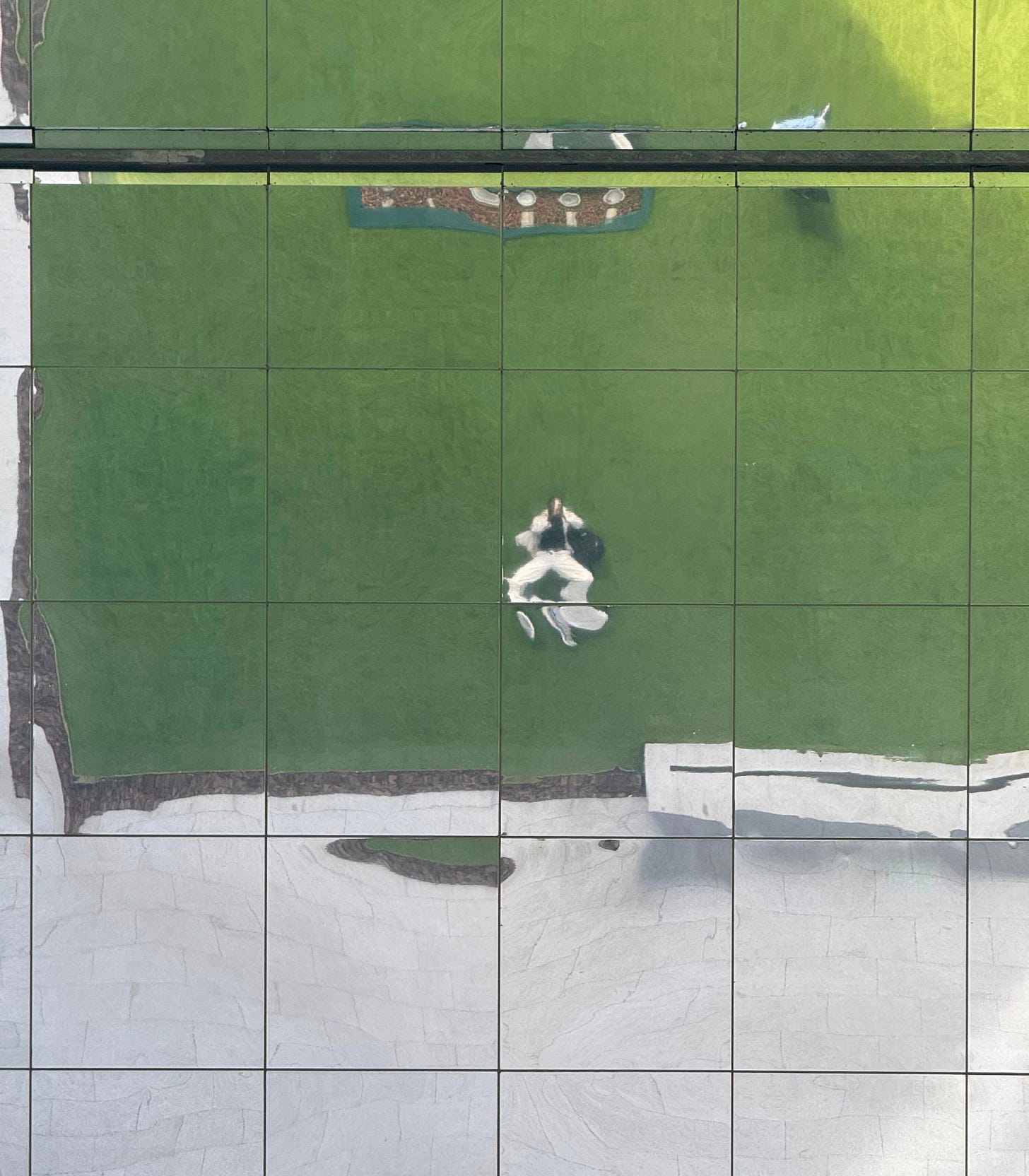

Remick’s dilemma is not dissimilar from most in a ‘creative industry.’ The Studio could have very much been The Atelier and focused on the head of a fashion house. Or, it could have been The Imprint and followed the life of an editor at a big publisher. It is so clear – so recognizable – that Remick yearns to be an artist. In the past, he probably wanted to be a screenwriter and/or director, but instead, he joined the corporate side with the studio in an attempt to get close to the art he dreamed about making without actually committing to it. But proximity to a passion isn’t the same as fueling it. In fact, a closeness to what you love without being able to puncture it isn’t pleasure; it’s torture. Remick wants to be liked by directors, so he withholds critical feedback that could improve their films. He wants to be seen as a part of the production rather than the smuck writing the checks, so he disrupts the set to ensure a single note of his is applied. His dream job has become a prison, while his passion lies outside of the cage he’s locked himself in. This results in bad movies. But, of course, this also makes great TV.

The adage "do what you love and you'll never work a day" doesn't hold for Remick. But does it hold for anyone else, either? By making his dream a profession, Remick finds himself further from the artistic output he yearned for, producing the very 'movies' he finds uninspiring instead of the 'films' that he loves. His situation reminds me a lot of a Billie Eilish song, ‘Getting Older’:

Things I once enjoyed…

Just keep me employed now.

Things I'm longing for…

Someday, I'll be bored of.

It’s something that I think about a lot as it pertains to writing. The pursuit of writing has freed me from deriving 100% of my creative expression from my day job, which, similar to Remick, is in a creative industry. But as my writing expands into a writing career — brimming with novel proposals, live readings, and brand deals — the path to monetization becomes clearer. More people read this newsletter than I can imagine, and I have yet to impose a paid subscription strategy, instead hoping that those who enjoy what I write will simply pay for it. But, behind this kumbaya way of deflection is fear, a fear that once I turn this into an engine of capital — which, I ultimately believe all good writing should be compensated for and that the writing on LOOSEY is great — that I’ll face the same double bind as Remick. Would I make different decisions if LOOSEY became a business? Would that impact what I write about or even how I write? How would that change what I consider to be ‘great writing’ as ‘great writing’ isn’t always the same as the most ‘monetizable writing?’ I guess the only person who knows the answer to these questions is me.

Plenty of writers claim to have turned their dream into a dream job, and I believe them. Maybe there is a way of doing this that feels closer to a dream than a cage once a paycheck is involved. But I do think money changes things. But that doesn’t mean I don’t want it…

In 2021, notably a year after we all tried to figure out the whole work-from-home-during-a-global-pandemic thing, The Atlantic published an article called “Loving Your Job Is a Capitalist Trap.” In it, Erin A. Cech warns about deriving your value from your employer. Instead, she wills us to find ways to prioritize our passion:

“I call the “passion principle”—the prioritization of fulfilling work even at the expense of job security or a decent… More than 75 percent of college-educated workers believe that passion is an important factor in career decision making. And 67 percent of them say they would prioritize meaningful work over job stability, high wages, and work-life balance. Believers in this idea trust that passion will inoculate them against the drudgery of working long hours on tasks that they have little personal connection to. For many, following their passion is not only a path to a good job; it is the key to a good life.”

Reading this now, my response is: yeah, duh. No shade, as the perspective is heavily rooted in COVID-era ideals, but in 2025, I don’t know how viable it is to wholly apply this logic when the job market isn’t giving what it used to and inflation (and the cost of eggs) is on the rise. With the introduction of quiet quitting and now rage quitting, the internet is full of suggestions on how to “stick it to the man,” but the reality is that you require money, but monetizing your passion can feel like a trap.

As we head into even more challenging economic times (girl, the tariffs!) against an already dire job market, we are going to have to re-evaluate our relationship to careerism and the concept of the “dream job.” I know it’s become trendy to respond with “I don’t dream of labour” when asked the question of “What’s your dream job?” but that statement has become so divorced from its original context that it doesn’t feel universally applicable.

Instead, I’ve seen a quote that feels more appropriate to our generation’s careerism crisis, a quote that connects the job market's previous failure to meet millennial post-graduate expectations with the current employment landscape for Gen Z and everyone else on the hunt for a job:

“Job market so bad might, I might actually follow my dreams.”

While I’m still trying to spell out exactly what that means for someone who likes having money and likes being creative, I notice that the words “job” and “dreams” are on the opposite end of the sentence. There’s something freeing in creating a space in between — the separation of church and state. A space where your mind can be rich with dreams. A dream that doesn’t need to be mined for riches. A passion that yields something that is just for you.

LOOSEY is a biweekly newsletter about culture, art, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

Something I've been also thinking a lot about is how most cool creatives with cool day jobs, like magazine editors, writers, directors, pour hours of their time and most of their efforts into indie projects for small audiences that are super high in their artistic value but don't pay much and then make an actual living from sponsored posts and commercial jobs. Like, no one makes money directly from their favorite projects and yet, these are the projects that affect status and indirectly bring money. Such a mindfuck when trying to prioritize opportunities, etc. ughhh

Great piece— it reminds me of a funny saying that my friend possibly misremembered but I find actually extremely profound lol “the prize for winning the pie eating contest is more pie”