On Boyhood

boyhood aesthetics with bieber, film cameras, dior mens, clipse, and eddington

There comes a point in a man’s life, roughly between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-two, when he decides to purchase a film camera. The camera becomes an extra appendage for the man, strapped to him like his shadow, accompanying him to various social functions: the beach, winter vacations, graduations, parties, and the like. I regret to inform you that I am just like the other guys.

To render my condition more universal (read: basic), my purchase coincided with a move to Brooklyn a couple of years ago, where, after a few months in a new zip code, I found myself at a used camera store buying a film camera that would quickly prove itself to be more faulty than functional.

A 35mm roll of Kodak Portra 400 has 36 exposures. To those of a particular generation, that might seem to be plenty, but to a generation pruned on an iPhone’s camera roll with a history of recording copious videos at concerts with zero intention of ever watching them back, a film camera is an exercise in restraint. I snapped photos sparingly, saving my lens for the most precious moments and most beautiful faces. I was lucky to find both in abundance. What I enjoyed most was the lack of immediacy, the delayed gratification of the end result – the image. It was always a surprise what I got back from the film studio, the underexposed images jogging my memory to extinct histories like an old diary entry. Some of those images even ended up in early LOOSEYs.

I wasn’t particularly talented, but I don’t think that was the point. The camera itself seemed to satisfy some condition, or more specifically, a return to tradition, that, whether I was aware of it or not, coincided with an innate wish to be perceived as a craftsman. What was a craftsman if not an upholder of a legacy? If I lived in the woods, perhaps I would have picked up woodworking; if in the suburbs, maybe I would have gotten into cars. But alas, I was in the city, and so, the Pentax Espio presented itself to me, like a pearl waiting to be plucked from an oyster.

Whenever I see a guy with a film camera dangling over his shoulder like a Birkin or raising a grainy VHS camcorder at a concert, I think to myself, “I cannot interfere; it is a canon event.” And yet, this experience, and others like it – cycling, espresso machine mastering, triathlons, and, maybe even the ancient art of podcasting – seem to be progressively universal amoung men of a particular age. These can be chalked up to just regular hobbies, you know, boy shit. But, still, I wonder if it could be a symbol for something more significant. The longstanding influence of Sofia Coppola’s cinematic aesthetic, Miu Miu’s increased profitability in a shrinking luxury market, the commercial success of Gerwig’s Barbie, the great Girls re-watch, the popularity of the WNBA, and the surplus of essays on “girlhood” are all recent examples of our booming cultural interest in the performance of womanhood and feminine adolescence. Could it be that “boyhood” is something that is also performed? Was there a defining aesthetic or doctrine that supplanted what it meant to be a boy? And if the fabric of masculinity is something that can be manufactured and exported, what are its most effective products? A focus on legacy and craft certainly isn't exclusive to one gender, and the standards for any identity are unreasonably high. But over the summer, I've found myself confronted with visions for boyhood, all seemingly connected, and I felt compelled to dissect.

Last weekend, a friend’s birthday party migrated into familiar territory for any frequenter of house parties: music video hour. Party members in the living room spilled into a semi-circle, taking turns punching songs into the remote to communally watch and remark. Finally, the troupe settled on the artist of the week, Justin Bieber, beginning with the breakout ‘Beauty and the Beat,’ as it features one of the best Nicki Minaj verses (“gotta keep an eye out for Seleneeeeer”), and finishing with the music video for DJ Khaled’s ‘POPSTAR,’ in which Bieber lipsyncs to Drake’s rhymes that correspond with the fellow Canadian’s road to fame (“You would probably think my manager is Scooter Braun, but my manager with twenty hoes in Buddakan!”). Between the two songs, there are seven minutes and seventeen seconds, but the duration between releases eclipses seven years. Even though the boy at the center of both music videos has evolved drastically, hallmarks of his practiced masculinity are present across the work: the steal-your-girl smirk, the erotic crotch grab, and the biting of his lip. Hallmarks that recur across a spectrum of men, becoming interchangeable across the likes of Michael Jackson, Odell Beckham Jr., Troye Sivan, Timothée Chalamet, and Tyler, the Creator. But, maybe that’s just more boy shit.

Bieber’s story is stitched with the fabric of manhood – the reinforcing of tradition, the maintenance of one’s own household – shepherding him from child star to teen heartthrob to husband. As he’s come of age, we’ve watched him negotiate relationships with the industry’s most powerful men – Diddy, Usher, Braun. Throughout this journey, where his well-being and commercial viability have been scrutinized, we’ve witnessed a boy sculpt himself into a man of his own image under the watchful eye of entertainment titans. If there is anyone who knows men and their power, it’s Justin.

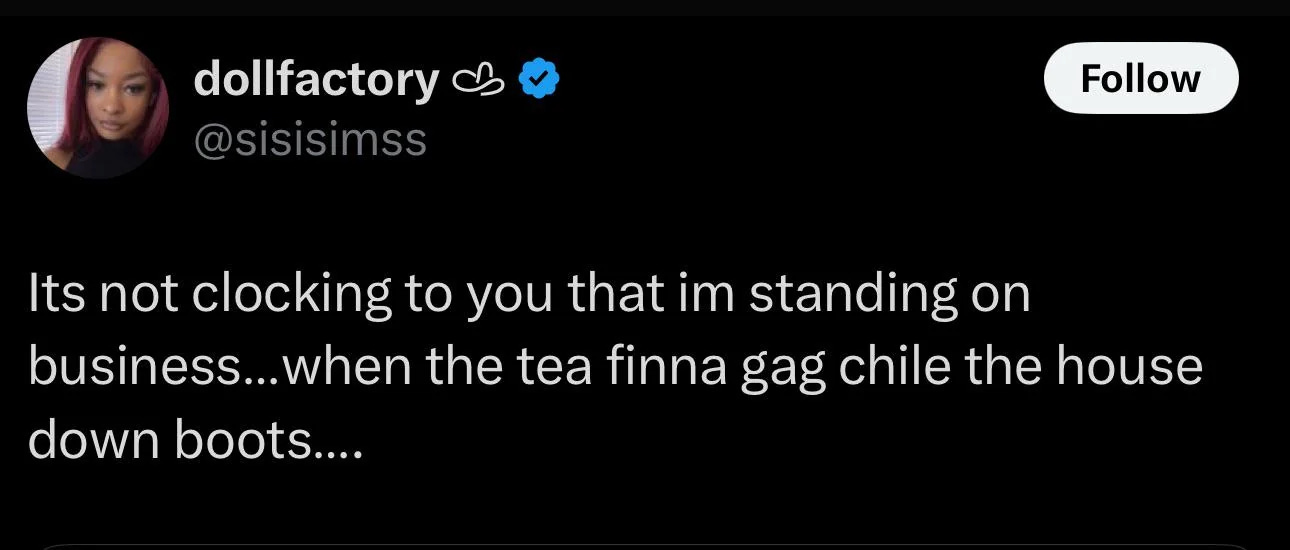

Six weeks ago, during a confrontation with the paparazzi, the singer spewed out a series of words that would go on to launch a thousand memes, track a surprise album, and spearhead its subsequent non-rollout: “It’s not clocking to you that I’m standing on business.” The words found their way into my mouth like oxygen, as they did for many, reworking themselves into a common lexicon like most misused AAVE – first ironically and then earnestly, erasing its melanated origins through the scale of the internet. What was most interesting to me was his rationale for the aforementioned “standing on business,” defined by the words he said before and after it. “I’m a dad. I’m a husband… You’re standing around my car at the beach,” he said. Bieber’s identity as a man, a provider, an upholder of a legacy and family unit, is what galvanized his remark. The car, the beach, the protector of property. I empathize with Bieber. The level of fame he’s amassed has cost him his solitude, leading to scenarios like this, where he’s forced to litigate his humanity in public. One cannot assume to understand every component that led to Bieber’s unique combination of words that night, but I reckon that it had a lot to do with his masculinity, a masculinity that has become both a beguiling trap and a lucrative platform as he pushes through adulthood.

His deserted scaffolding of boyhood is on display on SWAG, the latest addition to the Bieber oeuvre, arriving amidst divorce speculation, a $35.1 million separation from his manager, Scooter Braun, and his wife Hailey Bieber’s meteoric rise backed by a Vogue cover and the sale of Rhode cosmetics for a casual billie. I have always been a more casual admirer of Bieber and his talent, but this time, I was paying attention. It was clocking to me.

On SWAG, Bieber finds a home within the album’s tightly stitched alternative rhythm and blues production, serenading the listener through an airy set of songs that come and go like the wind. His voice, impressive as ever, is layered, reverberated, and pitched up in some cases, settling into the album’s atmospheric tone so that it feels as though you are cruising across its twenty-one tracks. The lyrics themselves lack density, but this adds to the project’s fluttering lilt, the slight verses making way for Bieber’s emotive vocal ability. At times, it sounds like an exhale.

Bieber orbits through the challenges of parenthood, marriage, and his faith, often at the brink of a breakthrough without exactly puncturing it. This is fine for a vibes-forward album; like a man, he points us to the wound but is hesitant to tell us just how bad it hurts. My favourites are the songs where I can identify his influences: the chipmonked “YUKON,” in which he summons the echoes of Frank Ocean’s “Nikes,” to the breezy “BUTTERFLIES,” where I had to scrub the credits for evidence of Ryan Beatty. (He’s not there). By tapping Mk.gee and Dijon, some of the most innovative newcomers in the alternative pop and R&B circuit, Bieber has created his most experimental album to date. The final output is more legible than his next-gen influences, readied with the accessible finish that ‘big tent’ pop music typically extracts, and yet it feels the closest Bieber has ever come to an artist statement. One of independence, reclamation, and devotion.

During his “Purpose Tour” of 2016, Bieber performed from the awkward confines of a glass case, symbolizing the walls of emotion that often resulted in him being misunderstood. With SWAG, one can only hope that he has released himself from the strain of the man-made box and come out the other side. On “DEVOTION,” he begins with “I’m starting to be open to the idea that you know me too,” signalling a softening summoned by a woman’s presence. And yet, aside from Sexyy Red, the credits do feel like a bit of a sausage fest. Maybe that is expected for a project about navigating the entrapment of manhood, one where Bieber is both trying to wrangle himself free from the pressures and pitfalls of boyhood and also live up to something greater. But, I’m skeptical if the two can live next to each other, side by side: the duty, the release, you know, boy shit.

If there is an album that points to another side of manhood, one built with confidence, rather than self-consciousness, and the joys of standing in your identity, rather than feeling burdened by it, it would be the latest Clipse album, Let God Sort Em Out. If you are planning on releasing a hip hop album later this year, just don’t. Delete those drafts. Get out of line. The Rap Album of the Year is here.

Brothers Pusha T and Malice have reunited after sixteen years to rap about EBITDA and focaccia, high ceilings and cocaine, penne alla vodka and lab diamonds under inspection. I listen to Clipse when I’m picking out lilies at the weekend farmer’s market and feel like an incredibly chic kingpin. This is the shit Kendall Roy was bumping before he backstabbed his father, Logan. It’s luxury rap.

Beyond their cutting lyricism, which veers from the humourous (“yellow diamonds look like peepee!”) to the lethal (“Calabasas took your bitch and your pride in front of me,”), what I love most about Clipse is that their art is founded on a set of strict ethics. There is an aesthetic consistency that you can trace back to their Hell Hath No Fury album that is present in their work today. There is a coded architecture that governs the way they write that extends to how they evaluate their peer set. Throughout the press cycle for Let God Sort Em Out, and within the work, the pair has been quick to take shots at those they deem fraudulent, namely Travis Scott and Drake, establishing them as morally bankrupt and not ‘real’ rappers.

To Clipse, their manhood is founded on the fierce preservation of truth within their personal and professional relationships as well as artmaking. You understand that they are living the lives they rap about. Remember, this is the same Pusha T who outed Drake for hiding a child on the 2018 diss record “The Story of Adidon.” This rigorous standard extends to how they view hip hop, which is as a craft, and not a trend. It’s something to be studied and upheld with mastery. On the now viral “P.O.V.”, Pusha T emboldens this distinction, sing-songing “They content create, I despise that. I create content, then they tries that!”

The product of masculinity has extended itself to this summer’s blockbuster hits, all similarly expressing a return to tradition and the preservation of craft. In F1, Brad Pitt assumes the role of a racing veteran who returns to the track to extend wisdom to a struggling Formula One team with a training plan rooted in substance and wit; in Eddington, two mayoral candidates of a pandemic-era New Mexico town go head-to-head in a battle of ego and values, with competing boundaries on where progressive ideals jeopardize historic rights, and, in Superman, a man balances a complicated history to fight to uphold justice and eventually save the day. Boy shit persists at the cinema.

The doctrines of manhood are integrated into the plot of these films, but what registered to me most was the aesthetics of the film 28 Years Later, the third installment of the 28 Days Later zombie-apocalypse franchise. I am not embarrassed to say that I rated this movie five stars with a heart on Letterboxd…but I am surprised. I love how the movie really went for it with the gusto of an angsty, stoned teenager. The visual language of the film, which was shot on a series of iPhones, drones, and camcorders, felt like I was inside a teenage boy’s head. The cinematographer used a technique called ‘bullet time,’ in which the camera revolves around a slow-motion action moment (think The Matrix) to provide the audience with a rotating angle of when a bullet strikes the head of a zombie. It is akin to an XBOX first-person shooter, perhaps fashioned after Call of Duty. But the most striking aspect of its boyish aesthetic was the music, almost entirely comprised of screamo and heavy metal, at times covering the Teletubbies theme song. It was cinema, transporting me to the Warped Tours of the early 2000s, something that I never experienced personally but understood to be in tandem with a specific type of boyhood.

It was strange, sitting in the theatre with a direct view of a presentation of boyhood that I was intimately familiar with but had never tried on. As a boy, I didn’t listen to much screamo, nor did I wear Vans, but I did scan the texts? Sure. Seeing it presented again made me wonder why I have not seen more of that aesthetic in the contemporary. The culture is rich with Y2K girl aesthetics: Nokia flip phones, the latest PinkPantheress and Addison Rae’s album covers, Petra Collins’ dreamy and youthful female gaze. These aesthetics don’t have to be gendered, and are often effective when not, but I am curious if there is a masculine equivalent today. Does the dated boyhood aesthetic of the early 2000s exist in 2025? Or did we kill it, like the rest of our youth, on our way to becoming men?

Maybe that’s why I have used the words ‘boyhood’ and ‘manhood’ interchangeably throughout this essay. It’s difficult to discern the difference as the tenets of manhood are propagated to boys at a young age. Be tough. Don’t cry. Be strong. You can trace the lessons thrust on boys to the foundations of modern masculinity. It is no wonder it’s so present across our media ecosystem today; the two are practically twins.

There are public figures who are working to redefine this. If podcasts are the podium for the modern male and his cultural interests, for every Joe Rogan or Andrew Tate within the manosphere, there is a Middlebrow or Las Culturistas attempting to broaden the aperture of what ‘boy shit’ can be.

Fashion designer Jonathan Anderson has made a career by confronting the confines of boyhood and masculinity across his namesake label of JW Anderson to his recent appointment at Dior. To know his work is to know that it exists at the borders of contradiction, dismantling expectations and prescribed doctrine with humour. This past June, for the debut of his Dior Men’s collection, Anderson’s first look featured a male model wearing a Christian Dior Bar jacket, an hourglass blazer that was traditionally fashioned for women. The clothes seemed both wearable and high concept, perhaps straddling both boyhood and manhood in a medley of Japanese denim, backward ties, high top sneakers and loafers. Anderson borrowed book totes from the women’s wear line, blurring again the gender ideals across the legacy French fashion house. But maybe, with such artful reference, Jonathan Anderson is just being a man and upholding tradition and craftsmanship. No longer skeptical, I see how the two can live next to each other, side by side: the duty, the release.

Last week, I developed a roll of film that had been wedged in my camera for nearly a year. I had been neglecting shooting, but thought to bring my camera on an upcoming trip to Marseille, which would mean I would need to address what was on the old roll of film. I assumed I used the film up, all 36 exposures, but upon developing, only seven photos were legible, the remainder eroded by overexposure. The surviving images are decent; grainy half-thoughts of me testing the camera on whoever is around me before ditching it and moving on to something else. I study the photos, the smirks of friends, the mess of an apartment. Not quite a craftsman, but ready to work towards it. You know, boy shit.

Thousands of people are reading ‘Come If You Want’ every week, my serialized novella on modern romance. Catch up on chapters one, two, and three before the finale. The final chapter drops on Tuesday, July 29th.

LOOSEY is a newsletter about culture, art, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

So many thoughts as someone who spent the start of the summer reading Judith Butler’s “Who’s Afraid of Gender?” with Lorde’s “Man of the Year” on repeat.

TLDR; version: It’s difficult to come to the realization that you can’t ever get off stage and all of life is a performance of some sort. But I’m all for the widening of the softboi as a legitimized form of masculinity as it helps tear down the binary and (I genuinely believe) is also healthier!

The one role I’ll never play is the dude who only shows his emotions during sports games, quietly hates his wife and dies of heart attack at 70 from suppressing himself his entire life.

This was such an interesting exploration (Ari Aster hive! 🙋🏻♀️🙋🏻♀️🙋🏻♀️).

The first thing I think of with Y2K boy aesthetics is boy bands. Oversized jerseys, a hoop earring in one ear, pagers (a lot of things, as you mentioned, "borrowed")... starting sentences with "girl."

Building the Band scratched some of that itch (I jumped when I saw someone named Landon wearing a leather flat cap backwards).