The MET's Superfine, 'Sinners' and the Cost of Living Forever

the dandy and the vampire, andré leon talley and america

Six brown bags wait patiently, as if ready to leave, facing the exit corridor in the last section of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Superfine: Tailoring Black Style exhibit. The scene resembles the final vignettes of a vacation, when your luggage lines the door, waiting for you to roll it home. The collection of bags, which is grouped into two, signals a homecoming of sorts across generations.

The first group immediately renders its significance to me – a trio of ‘chocolate’ Telfar bags. I know why they are here: a symbol of Black independence and New York, frequently seen on the go, in the airport, on the subway, on Beyoncé, of all places. But the bags’ coupling with the second set of luggage brought forth a new meaning.

My knowledge of the second family of bags comes entirely from historical images: a collection of Louis Vuitton travel trunks, licked with the initials ‘ALT,’ for the late Vogue editor-at-large André Leon Talley, “the last editorial custodian of unfettered glamour.” A symbol of Black progression in a predominantly white fashion industry. The gold-painted lettering leapt from the LV monogrammed trunk, introducing itself before the French fashion house, whose logo served as its foundation. The initials’ bold proclamation, bolstered by the legacy of its late owner, whose impact haunted most of the exhibit, signalled a different kind of Black ownership and pride than the Telfar bags, one propagated, and, perhaps, entombed by a white institution. Were André’s bags significant to the MET because he had once owned them, or were they significant because their owner had amplified his namesake, his ‘respectability,’ with the associative lift of institutions like Louis Vuitton?

Since previewing the exhibit at a private press conference on the first Monday of May, I have returned to the image of the bags to try to parse the relationship between Black independence and institutionalized patronage. As I watched celebrities ascend the steps of the MET Gala, in garments under the related theme of ‘Tailored For You’ — some in independent Black designers and others not — I weighed the relationship between artist and agency, expressionist and sponsor. The bags were positioned together to signal Black ownership, yet I found myself trying to determine if their pairing was one of comparison or contrast. ‘Ownership’ and ‘being owned’ are two different things, but perhaps the bags already knew that; they were facing the door, ready to leave.

The conflicting bag display is a precise metaphor for the protagonist of the exhibit: the Black dandy. Within his dress lies a curation of contradictions that play on formal aesthetics and a reclamation of the self.

In her book “Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of the Black Diasporic Identity,” professor and MET guest curator, Monica L. Miller relays how the dandy deployed fashion as an act of silent protest and ‘sartorial revenge,’ and, through centuries, liberated himself through style. The exhibit, which draws from her book with indulgence, thoughtfully takes the viewer across twelve sections of Black tailoring and style, split into themes such as Ownership, Distinction, Beauty, Disguise, and Freedom. The exhibit features archival items – garments from the estates of André Leon Talley and Prince, oil paintings, and historical texts – as well as special costumes fashioned by contemporary designers such as Grace Wales Bonner, LaQuan Smith, Maximilian Davis, Telfar Clemens, and Raul Lopez. The items from the exhibit, as well as powerful essays and images, are captured in an accompanying exhibition catalogue, with photography from friend-of-the-letter Tyler Mitchell. In short, the exhibition experience was marvelous.

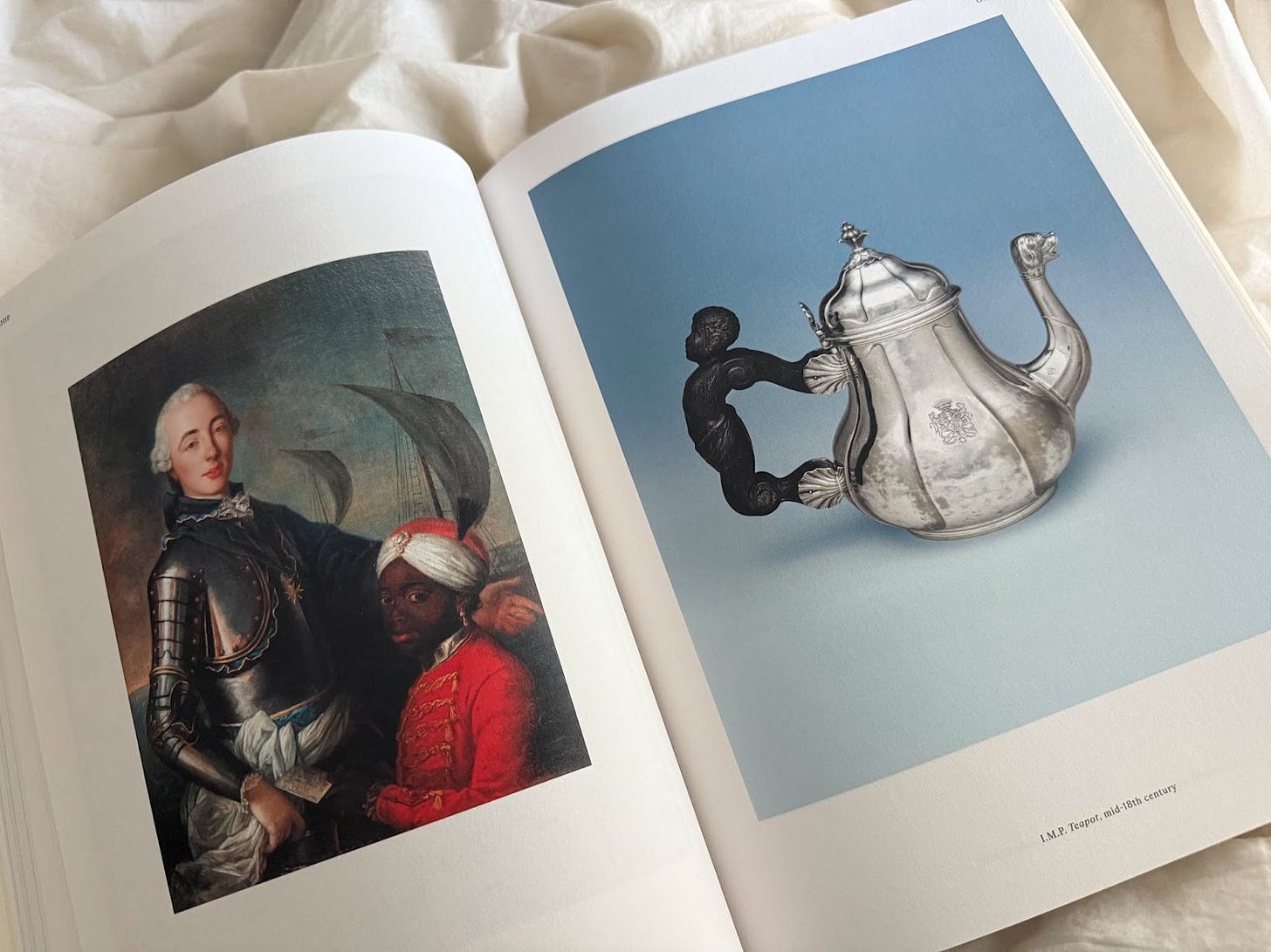

Within the Ownership section, I learned about dandified slaves — enslaved companions who were cloaked in expensive garments by their masters and, at times, even educated. These “luxury slaves” were not subjected to domestic labour but still were property of the household, acting as ‘civilized’ companions. They were stock characters, serving as exotic accessories and ‘playthings’ for their master.

Adrienne L. Child expands on the role of the dandified slave in the exhibition catalogue:

“To own a black attendant was a form of conspicuous excess that signified wealth, a taste for the exotic, and possible colonial connections. Black servants, frequently adorned with a passcode of feathered turbans, pearl earrings, and sumptuous livery, were conventional accessories to white aristocratic sitters in paintings from the seventeenth century onward… This ubiquitous persona demonstrates how style, ornament, and exotic flair can obfuscate the political dimensions of Black servility, normalize the horrors of colonial enslavement, and control the enigma of the Black body.”

The dandified slave’s complicated relationship to his clothes returns me to the styling of the brown bags in the MET and the question of ownership. His pristine collar signifies a proximity to status, but it also acts as a leash, attached to the institution he serves. There is agency that comes from being fashioned by others, but perhaps even more when you can fashion yourself. As much as the opulent dress could oppress, as it does through Child’s inspection, there was a chance that it could also liberate.

The MET’s exhibit borrows the name ‘superfine’ from a 1789 memoir published by Olaudah Equiano, who saw fashion as a way to challenge stereotypes and assert self-worth. The catalogue continues with the following excerpt on Equiano:

“Enslaved in West Africa at the age of eleven, he was transported to the Caribbean and eventually to colonial Virginia, where he was bought by a British naval captain. He sailed on British warships for a number of years until he was again sold… Equiano's travels taught him the value of letters and numbers; he also knew his own worth as an experienced, literate sailor who was well-versed in the merchants' trade. Equiano began to buy, sell, and trade goods on his own in the hope of saving money to purchase his freedom.

When he had assembled nearly all of the funds and emancipation appeared certain, he explains in his autobiography, "I laid out above eight pounds of my money for a suit of superfine clothes to dance with at my freedom." For Equiano, a "suit of superfine clothes" would be made from finely woven wool, an expensive luxury item, and it would be a manifestation of his newfound ability to define his future self. To procure and wear this particular form of dress represented liberation for him a decisive and poignant moment of literal and metaphorical self-fashioning.”

To be a dandy is to wrestle with institution and independence across the borders of the Black imaginary. This has a cost, but what Equiano teaches us is that a dandy who knows his price can also buy his freedom. Whether I am looking at ownership through the lens of an LVMH co-sign or from the independent marksmanship of a Telfar bag, what the Superfine exhibit does magnificently is create a vessel to interrogate power.

What does it mean for the MET’s Costume Institute to center Black style in 2025, amid fascism and executive orders that halt diversity, equity, and inclusion programs?

What is the significance of the MET raising $31 million from donors and sponsors who were galvanized to support Black style and capitalize on this cultural moment?

How do we celebrate this landmark achievement and not relate it to the ‘conspicuous excess’ that Child’s wrote about in regards to the owner and the dandified slave? And how does that translate to those invited to the MET Gala and by whom?

What does it mean for Doechii to brand Louis Vuitton on her cheek at the MET Gala, conjuring images of scarred slaves, while wearing a garment inspired by the most notorious, formerly enslaved dandy of the 1700s?

These are the questions I have been wrestling with since visiting the exhibit almost a week ago. Before entering the exhibit, I had the pleasure of hearing from Monica L. Miller, who spoke warmly about its preparation, the historical importance of the dandy to American culture and style, and how the beautiful contradiction of the dandy serves as an allegory for Blackness in America.

Miller quoted various texts within her speech. A passage that stuck with me was from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, in which the narrator spots three young Black men on a subway in zoot suits. A teacher says to the narrator, “You're like one of those African sculptures, distorted in the interest of a design." He then thinks: “Well, what design and whose?”

The question of ownership once again. Another question I do not have the answer to.

While Trump attempted to annihilate the National Museum of African American History, Sinners was #1 at the box office.

I saw Sinners later than most, waiting to watch it on one of the two IMAX 70mm screens in the country (flex). Once again, I found myself in awe of Coogler’s ability to blend cross-diasporic history and folklore to create supremely spirited and original entertainment. Cinema is back, baby!

Set in the 1930s, the film follows twin brothers who return to their Mississippi hometown with ambitions of starting a juke joint. As they build the establishment, employing members of the community with the hope of investing in their collective independence, a troupe of white vampires stalks them. The vampires are relentlessly set on enlisting the brothers and their primarily Black clientele in their growing army through gruesome vampire bites.

The lead antagonist, and threat to the community, is an Irish vampire named Remmick, a skilled manipulator who spreads the vampiric contagion. His bitten community becomes institutionalized in a crazed fever, losing themselves to the homogeneity of supernatural control and bodily impulses. Remmick’s character is a stand-in for assimilation, the way Irish and Black American history mirror each other under the foot of white supremacy, and he weaponizes this relation to gain allies. He offers the twins an opportunity to be ‘protected’ under a new construction of power, but similar to the narrator in Invisible Man, we are left wondering: “Well, what design and whose?”

It’s a strong parallel to the tale of the dandy and this year’s theme at the MET. The bloodthirst of the vampire is comparable to the cultural extraction of Black culture and life in America. Much like the governing institutions of this country, Remmick offers power and legacy. In the film, we watch as one twin falls victim to Remmick’s vicious bite while the other frees himself. The battle mimics the dandy, who must dance with the institutional promises of those who want his resources while keeping his independence ablaze. In this sense, the dandy is both twins in Sinners, the one bitten, who gets to live forever, and the one not bitten, who gets to be free. At once, the contrast of the brown Louis Vuitton trunk and the brown Telfar bag coheres for me. To be Black and hold power in America is to understand that you cannot have one bag without the other.

During the opening remarks of the Superfine press conference, acclaimed actor and MET Gala co-chair Colman Domingo shouted out a variety of contemporary dandies. The dandy that received the loudest applause was André Leon Talley. The exhibit and the MET Gala persist under the shadow of his golden caftan. His spirit lingers over the year’s urgent theme, a theme that I applaud the institution for tackling so beautifully during this critical point in history. André’s presence, upheld by those who remember him and institutions like the MET, becomes everlasting. His items are bartered over and preserved by various governing entities, and his words are republished to reach the masses and the pockets of donors. André Leon Talley’s body of work, pulsating with life and cultural impact, becomes drained, extracted like blood from a vampire’s kiss. In return, he will live on forever, reminding us that to become a legacy, you must first die.

LOOSEY is a biweekly newsletter about culture, art, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

this was as thoughtful and honest as i expected it to be. may we get to read your observations forever and ever.

This is such a great and enlightening review. Thank you for writing it. I also recently wrote a story for ARTnews on the depiction of the Black dandy in art over the past 300 years. I write about the Roch Aza painting you feature on image 5, which depicts an enslaved boy from Martinique to the Rohan-Guéméné family of France. I hope I get to visit New York before the Superfine exhibition ends https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/superfine-met-museum-costume-institute-black-dandy-1234740801/