Can You Build A Home Without Wrecking Your Own?

the brutalist and bad bunny's meditations on home and migration

If you have completed the LOOSEY reader survey, thank you! If you haven’t, you still can right here. It’ll only take one minute — I promise!

Returning to your childhood home, during the holidays or under any circumstance, is like finding an old pair of pants and attempting to try them on. Beyond the humiliation that comes with sleeving your limbs through ill-fitting, out-of-style clothes, you are forced to experience how much you’ve changed, grown or not grown, and if the new pants you’ve opted for fit your ass better than the old.

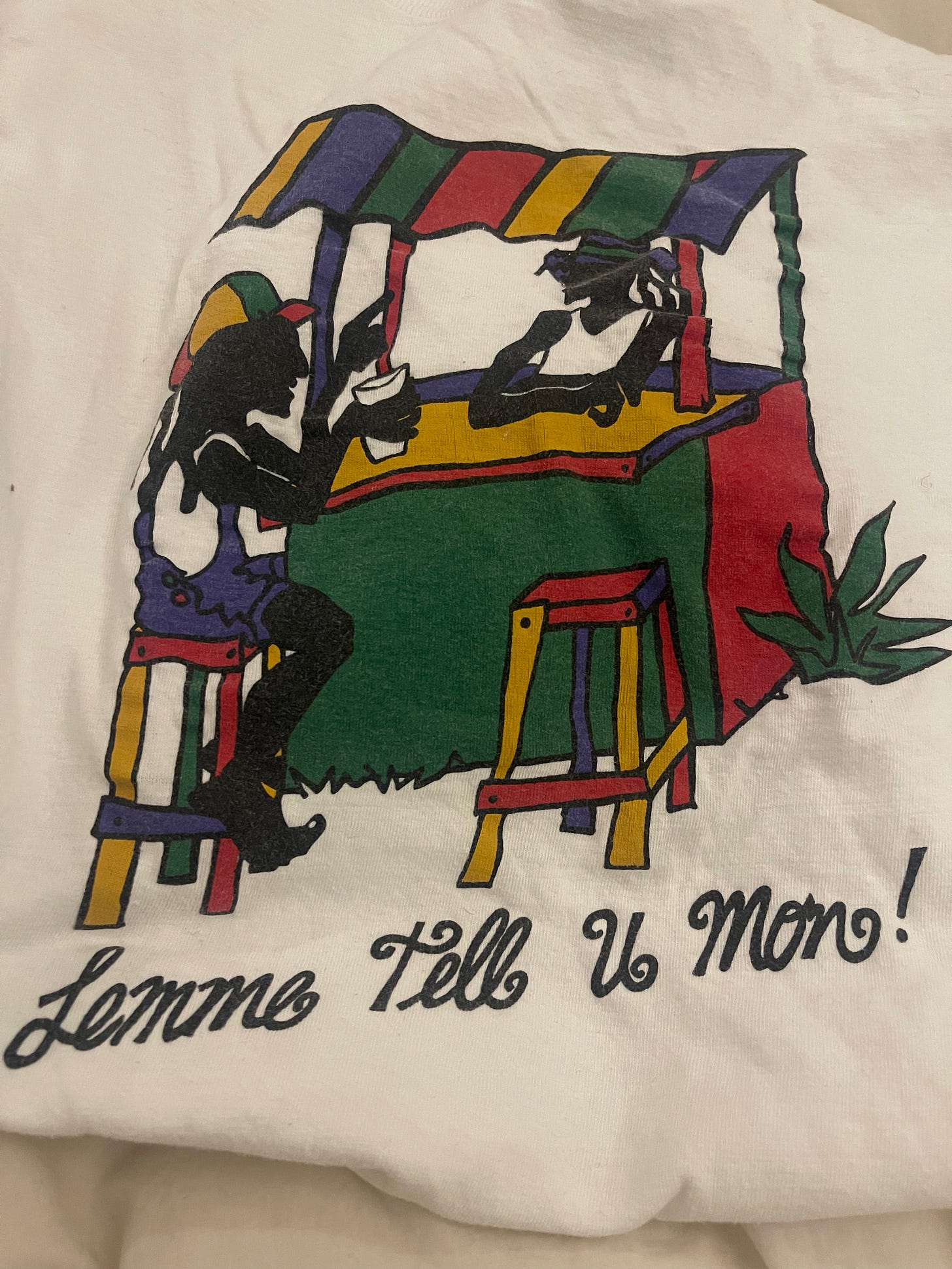

After spending a portion of the holidays in the house I grew up in, I returned to my apartment with no old pants (I’ve worked on my ass since childhood), but with a collection of t-shirts that used to belong to my parents. I was pretty enamored with this Jamaican national football team shirt:

On the first Saturday of 2025, back in New York after two weeks in Canada, I rode the train uptown to a spacious AMC theatre to watch The Brutalist with one of the new (old) t-shirts layered beneath a woolly sweater.

The Brutalist drops us off at the tail of László Tóth’s voyage into the United States, supplanting us in the Hungarian-Jewish architect’s immigration. The Holocaust that Tóth has escaped is alluded to but never overtly mentioned by the titular brutalist. Instead, he focuses on the future: finding work, and pursuing the American Dream. The film ignites in 1947 and halts in 1980, catapulting the audience through the triumphs and pitfalls of Tóth’s life during a three-and-a-half-hour epic.

In America, Tóth attempts to reconstruct a home for himself by building other people’s homes. We witness false starts and blips of success as he finds work at his cousin’s furniture store, a construction site, the renovation of a chic home library for a wealthy industrialist, and, eventually, the major development project of a community center – equipped with a gymnasium, chapel, and theatre – in Pennsylvania. The latter allows him to apply the full magnitude of his talent while acquiring assistance to bring his wife, Erzsébet, and niece, Zsófia, to America.

The film’s inside joke is sick yet timeless: a country requiring the hands of immigrants to build homes they would otherwise never be allowed in. Throughout the film, Tóth is reminded that his differences are only ‘tolerated’ because of his talent.

The film is divided into two parts, with a fifteen-minute intermission between them, and concludes with an epilogue. The Brutalist’s sweeping cinematography choices – the establishing shot of the upside-down Statue of Liberty, the long take of Erzsébet’s dinner intrusion at the top of the second act – against the aforementioned formulaic structure buoy the audience in the fractured mental faculties of Tóth. His mind is blistered by America but also confined by it. We experience the glees and crashes of Tóth in Tom and Jerry-like dramatics. Like steel, his malleability becomes hardened by the relentless pressure of his new country, rendering him austere and cold like the structures he creates.

The first half of the film portrays the misguided optimism of the American Dream while the second half reveals the Dream’s dismantlement. Although the film’s ambitious length and “extra” form have been contested, I believe it’s an effective choice. On the film’s duration, the director Brady Corbet remarked:

“I don't understand why...it's okay for [superhero films] to be three hours long, and yet when you're making a drama about adults for adults by adults, that it's like, 'Well, you have to mop this all up in 90 minutes.’”

Although snarky, I agree. There are certain films this season that are skating by on style alone, so much so that the length is challenging but, for a film with a substantive edge and spoiled with glimmering visual direction, The Brutalist fortunately doesn’t have to.

In the movie, the aspiration of home is a constant gamble for Tóth and his family. How long can they persist in America? Are Tóth’s expectations of the country worth holding out for amid the onslaught of disappointments, or should he cut his losses and leave? Both Erzsébet and Zsófia become unhappy in America, expressing concerns if they will ever truly be welcome and, through different degrees, suggest migration to Israel. But Tóth, despite the setbacks, is playing the long game. True American grit.

His story is every immigrant's story: a game of investment, one where your only choice is to trudge forward in pursuit of the dream even though the dream itself may be a mirage. A fool’s errand where one cannot afford the mental exercise of ‘What if I go back?’ Picasso once said that “every act of creation begins with an act of destruction” and the putty that Tóth is beaten to eventually becomes the clay moldings of a new man. Like every immigrant, he is equal parts homewrecker and homemaker.

The West is unkind to Tóth, unkind to his family, unkind to his mostly silent, subservient Black bestie/lover1 but perhaps kinder than what he is running away from. But will it ever be home? That’s the parabola the film leaves us to wrestle with on our own.

At the beginning of the film, on his first night in New York, Tóth is told that his “face is ugly” by an American sex worker. He smiles impishly and responds with an endearing “I know it is.” Towards the end of the film, when he is soured by America, he points the finger back at a rival American architect and says “Everything that is ugly, cruel, stupid — but, most importantly, ugly — is your fault.” It’s a cutting line delivery by Adrien Brody, full of bile and humour. With this, it’s clear that he’s responding to the meddling architect’s design but, in the context of the film, I imagine he is referencing the country's stain on its inhabitants, too.

Contemplations of home are all over Bad Bunny’s latest album DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS. Rather than striding forward like Tóth, Bad Bunny gestures to a Puerto Rico of the past, before the island was pillaged by gentrification. The cover art references the plastic chairs that Caribbean aunties and uncles typically sit on and yap. The album’s accompanying short film depicts an elder Puerto Rican man struggling to keep pace with an island that has shed much of its identity. Bad Bunny theorizes the imperceptibility of nostalgia and a longing for a culture that nursed you but you were never present for. Much like The Brutalist, the destination the music artist pursues will never be reached because it too is a dream. It slips through his fingers as he strains to grasp it. I think of my inability to make my mother’s Jamaican oxtail or the fact that I could quite never replicate my grandmother’s patois and, draped in a Bajan t-shirt from my father that says ‘Lemme Tell U Mon,’ I understand at once. A screaming vacancy born out of disconnect and displacement.

Bad Bunny slides onto a salsa beat with confidence on “BAILE INoLVIDABLE,” channelling the music of his elders. He bellows with sorrow and regret against a stuttering horn and wandering piano. His voice is possessed by a force beyond his years and he meets his band’s refrains with a rhapsody of his own. “No, I can’t forget you. No, I can’t erase you,” his band sings in Spanish.

My (current) favourite is the album’s bodacious opener “NUEVAYoL,” an homage to the Puerto Rican neighbourhoods of New York. Bad Bunny shouts out Borican cultural landmarks over a sample of “Un Verano en Nueva York" by Andy Montañez and El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico. The song pulses with the longing for a lost identity with the modern delights of what migration has afforded him. For a track simmering with gyration, its biggest crime is that it isn’t released in the summer. Regardless, something tells me it will carry me to the warmer months. We haven’t had a song of the summer hit so hard since “Wild Thoughts” and Rihanna isn’t doing anything to defend her title so… go ‘head, Benito.

The album title translates to “I should’ve taken more photos,” referencing a yearn for the places and people who characterize a home that is no longer with us — whether that home be an actual place or the tight squeeze of a loved one. But the album evades being interpreted as a Make Puerto Rico Great Again gimmick. Instead, it’s something more withstanding and rooted in contemporary truths. A bitter acknowledgement that the fruits of the past may be out of reach before we’ve acquired its taste. As a result, the album is more of a eulogy than a love letter. A place of mourning and memories. An altar.

It is worth noting that in both The Brutalist and DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, the protagonist's erosion of identity is the price of entry for his advancement and assimilation into America. The barter of one home for another. But this isn’t just an ‘American’ experience, it’s an immigrant experience.

This week, I clocked in four years in America, four years in New York. And even though I am grateful for the life I’ve designed for myself, The Brutalist and Bad Bunny force me to acknowledge that the concept of ‘home’ is always changing.

I don’t know if it’s possible to litigate the past while being committed to a new future. Perhaps, that’s just the immigrant’s dilemma. But something tells me, immigrant or not, we are all going to have to become comfortable with moving forward, physically and mentally, to make it through the years ahead. Amidst the wreckage of homes destroyed by natural disasters and conflict, our understanding of what constitutes a home will remain elusive. Maybe that's just the way it’s always been.

If you can, consider donating to Doctors Without Borders to support hospitals and civilians in Gaza or provide internet access through eSIMS in Gaza. Also, here is a round-up of where you can donate to help those displaced by the fires in Los Angeles.

LOOSEY is a bi-weekly newsletter about culture, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

I don’t want to spoil anything but let me know if the comments if you clocked it too.

Brendon, this made me feel so seen.

I'm an immigrant too. From Ukraine. The line “I should’ve taken more photos" just destroyed me a bit.

Your ability to draw profound connections between two seemingly unrelated pieces of art is nothing short of remarkable. This observation: “erosion of identity as the price of entry for advancement and assimilation into America” is one I’ll be carrying with me for a long time.

Thank you for capturing these complex emotions so beautifully.

Epic! I’m an immigrant (from Haiti) and

I’ve been struggling with all the emotions and feelings that you articulate in this piece. Thank you for giving me the words to describe my experience.