Salt Looks Like Sugar

'perfection,' miu miu, skims, the 'west village girl' and identity as a place

That breakfast at the Chateau Marmont when I wrapped my teeth around a strawberry compote-coated knife and yanked it out clean like Excalibur from a stone, I considered blowing up my life. Not destroying it completely, as there were many things I wished to preserve, like the stuff I jotted down in a journal under the title of ‘Things I Am Grateful For’ whenever I needed centering, but re-imagine it, the ‘it’ being my life, and perhaps do it in Los Angeles, of all places.

I wouldn’t understand this yet, but I had never really committed to any place since high school, cycling through Kingston, Lisbon, Toronto, Singapore, and now in New York, the latter just eclipsing the four-year mark. Getting comfortable felt uncomfortable, and I was beginning to feel restless. A change in scenery was a part of my constant need for reconditioning, trying on new locations like t-shirts. A woman I once paid one hundred and thirty-five dollars to pull cards and read my birth chart told me that I had plenty of Scorpio in my chart, which meant that I was constantly transforming, disrobing my identity like the skin of a snake. This made sense. But I suppose that is what I had paid her to do, to make sense of things.

I had been to Los Angeles plenty of times. Before this trip, I struggled to come to an opinion of it and, lazily, considered it – quite plainly – ‘not New York.’ I understood this to be a rather ignorant moniker for a city rich with its own lore and cultural capital, but for someone coming from Canada, the binary of America split itself between two coasts, and only one had Dallas BBQ. And so, I chose New York.

However, during this brief trip, fresh off the heels of a long weekend in New York spent toiling over manuscript edits between dinners at The Odeon, Los Angeles, and its sprawling geography, marked by haunted canyons and broccoli hills, began to click into place for me. I could, as they say, ‘picture myself there.’

In an Uber, mid-voice note, a nest of bikers closed around the car next to me while stopped at a red light. The leader of the biker gang – although I couldn’t have known that he was the leader, other than he was simply the most attractive, and therefore, I granted him that authority – collapsed his fist on the window of a neighbouring car. He was angry, legible to me by his shouts that permeated my windshield. His tantrum, warranted or not, was being recorded by his lackey, equipped with his own set of wheels and of lesser handsomeness; the recording of the confrontation gestured to me that he was prepared to cause a scene. The car of interest sped off, flushed in the rubber wheels of escape, and the bikers followed, leaving me and my Uber driver to imagine what came next. The bikers and the targeted car disappeared, but the violent strum of their engines and the banshee shrieks of their tires stayed with me. Later, after dinner, at a restaurant where the founding chef was reported to have a fetish for skinning cats, my cab trailed a man barrelling down Sunset Boulevard. He was tucked into a vintage keylime-coloured car, his hair tousled by the wind, while his car’s gasoline skunked the air. My driver rolled up the windows, but I inhaled greedily, anyway. Maybe that was when it began to click for me, when the disparate images of Los Angeles began to fasten itself into a picture with me at its center. The cars, the chase, the crooked ascension of Laurel Canyon as it winds you up to Mulholland Drive – that was Los Angeles. No longer ambivalent, I loved it.

Back at the Chateau, I try on the identity of Los Angeles the only way I know how: by consuming. I order a green juice and fire up Didion’s Goodbye To All That, her famed essay on leaving New York and moving to Los Angeles.

I begin to write this essay. The green juice travels to my mouth through the double-barrel of a black straw. My pen moves across the page feverishly, and the strawberry compote and the pain au chocolat that accompanied me are gone by the time I lift my head. I ask for the bill and leave. This was only last week, but was anyone ever so young?

Identity attaches itself to a place in two directions, backwards and forwards. After you’ve spent time in a place or return to an environment of significance, you can trace the facets of yourself within the setting like an anthropologist. You notice that mannerisms and ticks that you thought were uniquely yours were endemic to all of its inhabitants. Even though you’re looking in the rearview, it’s a mirror, and a mirror, by nature, reflects. But place also reveals itself in a forward motion, as it was with the vision of Los Angeles I held for a few days. It can project an image of your future, a portrait of a different life, should you choose to be a blank canvas. We usually see ourselves as the fixed unit and place as variable, but there are times when a place’s presence — its fixed imagery — is so vibrant that it can cause us to flex. In such moments, we become the muse, a snake that wiggles into a skin not of its own shedding but of its environment.

The concept of ‘identity as a place,’ and the ability to shed it through migration, is explored in Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection, an Italian work of fiction that was shortlisted for the 2025 International Booker Prize. Within its pages, we follow Tom and Anna, a twenty-something-year-old expat couple who live in Berlin. The novel’s subjects are familiar but opaque, rendered in such a way that we understand that they are people as much as they are symbols for the ‘millennial creative professional.’ Their hollow characterization – unsupported by dialogue, as there is none in the novel – allows us to project ourselves, and those we know, onto them. We understand that Tom and Anna come from a specific part of Europe, but the novel’s stencilization of them lets us know that they could have come from anywhere. They are skeletons, and we are the flesh. Even though the novel occurs in the mid-2010s, part of its success is that it feels applicable to the post-pandemic remote work and ‘digital nomads’ of today.

In the prime of their twenties and riddled with the possibilities of a new city, Tom and Anna are eager to try on Berlin. Much of their identity is depicted by what they consume: the art gallery parties on Graefestraße, the late nights at Berghain, drunk eats at the Turkish market. They work from home; they volunteer during the migrant crisis; they Airbnb their flat when they travel to neighbouring countries; they DoorDash takeout when they are too hungover to cook. The life they’ve built, supported by the cultural backbone of Berlin, gives them a sense of pride, a feeling that they are ‘not like the other girls’ of their hometowns, even though they contribute nothing to the culture themselves.

Throughout the novel, the couple’s life and career persist through images on social media – the creative assets they design for clients that exaggerate the appeal of the brands that pay them, but also the performance of their own identity and expat lifestyle on their personal Instagram pages. The main character of their digital portraiture is not just them, but specifically them in Berlin, as they absorb the local culture as their own. Throughout the novel, Latronico is sure to emphasize the contrast between the reality of their life and the images they post.

There is a dotted line between the consumerist gaze of Tom and Anna and the recent portrayal of the ‘West Village Girl’ in New York Magazine, a much-debated cover story that characterizes a specific brand of young woman who lives in one of Manhattan’s most Instagrammed neighbourhoods. In ‘It Must Be Nice to Be a West Village Girl,’ writer Brock Coylar describes the homogeneous pack of women as:

“Young women of some privilege, posting and spending their mid-20s away. They all seem to keep impressive workout routines, have no shortage of girlfriends, and juggle busy heterosexual dating schedules. They work in finance, marketing, publicity, tech – often with active social-media accounts on the side. They have seemingly endless disposable income. They are, by all conventional standards, beautiful. Occasionally, they are brunettes. Whatever their political beliefs, their lives seem fairly apolitical.”

This, existing in the exhaust pipe of cultural displacement of the diverse artists that used to make up the West Village, frames the story as an effective parallel to Perfection. An analog to how identity moves throughout a neighbourhood, onto its inhabitants and onto their grids, for better or for worse.

As Perfection stretches quickly across the years, we witness the continued gentrification of Berlin. Nomadic creative professionals are slowly replaced by nomadic tech workers, and the lingua franca becomes English as newcomers from New York, Sydney, and London trickle in. Freelancing for Tom and Anna becomes tough, the rent becomes high, and the picture of Berlin they’ve stepped into begins to fit them oddly.

They look for new places to consume. A new adventure to try on, trying to replenish their slippage of identity in a new place like Lisbon or Sicily. The novel ends on a punchline that I won’t ruin, that is legible to the reader but not yet to Anna and Tom as they embark on an exciting venture in a new city, with the potential to not only enrich their professional and personal life. Their Instagrams, thankfully, maintain their luster.

The construction of the novel showcases how identity is extracted from a place, but also who is privileged enough to extract it. It depicts how identity and environments can be commodified to look like something they’re not and how empty that can feel in the end. Tom and Anna are presented to us without bias. We aren’t meant to dislike them. Only when we extrapolate that their tendencies are emblematic of a broader, all-consuming, ‘always online’ archetype does the novel feel like an indictment. Through Perfection, identity-as-a-place not only moves in both directions, backwards and forward, but in a third space as well – online. Regardless of their circumstances, Tom and Anna can architect their environment for digital consumption, and in the end, this satisfaction is just as satiating as their lived reality.

The digital construction that we see in the novel and the commodification of the self through images go hand in hand with the homogeneous flatness of adopting an identity of an environment, be it Los Angeles, the West Village, or Berlin. The portrayal of these identity markers is rarely as withstanding and satisfying as the reality, and yet, much of today’s culture is based on this. This tendency is addressed directly in the thesis of Miuccia Prada’s Miu Miu Spring/Summer 2025 collection “Salt Looks Like Sugar.”

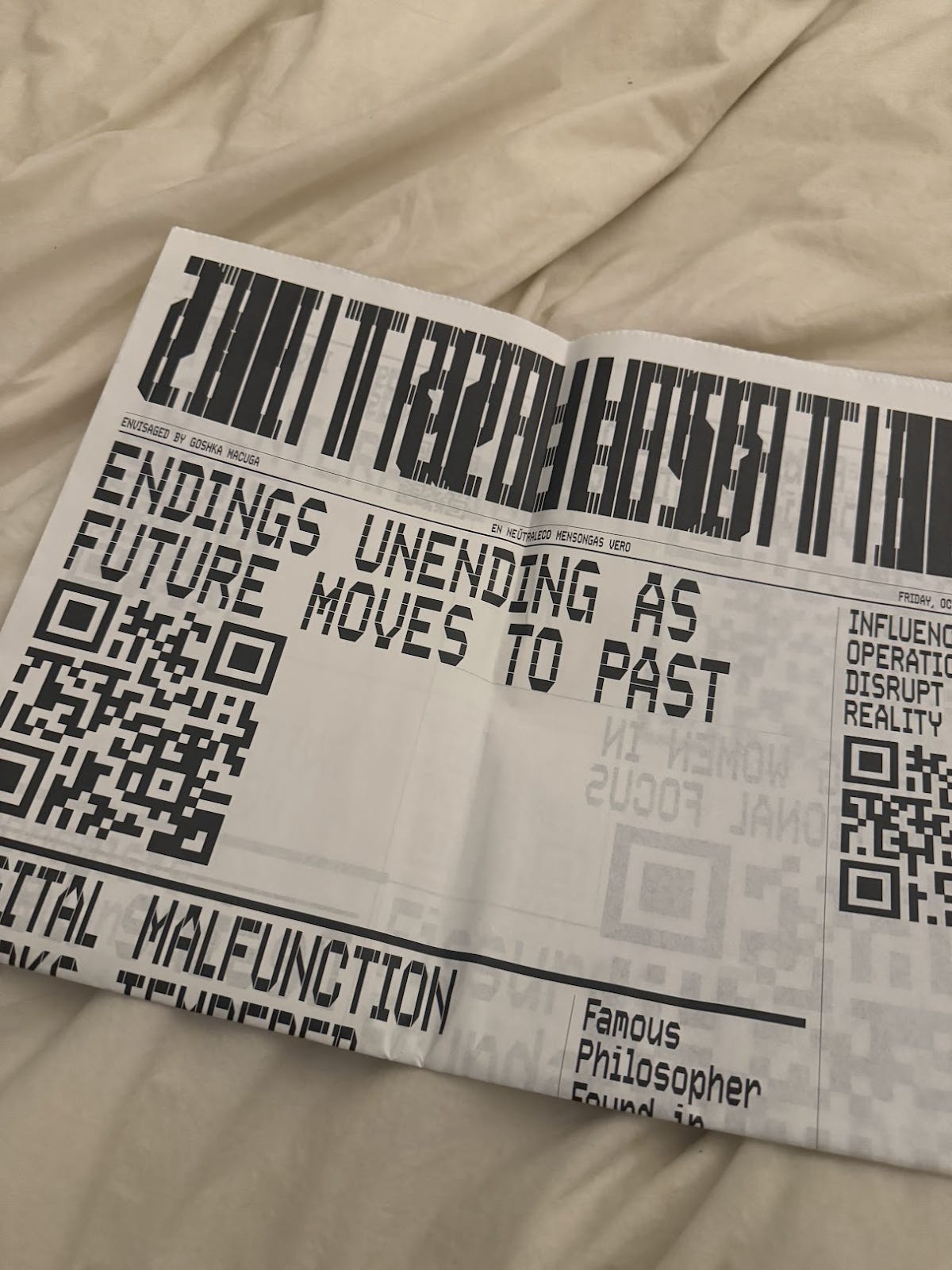

In an exhibition with Polish artist Goshka Macuga surrounding the collection, Miu Miu calls us to decipher the concept of truth within the deception of image and appearance. On a practical level, this is accomplished through the collection’s fabrics, materials that look as though they are constructed of nylon but are developed using high-quality silk, for example. This is also achieved conceptually, as above the runway space hung ‘newspapers’ developed by Macuga called The Truthless Times, reminding us to delineate what is fact from a world of misinformation. The name, “Salt Looks Like Sugar,” directly addresses how one thing might falsely appear as another. The metaphor of a fictional newspaper, a feed of information that exists in a canopy above the runway, is synonymous with the social feeds of today, feeds that are saturated with not only manufactured images, like the posts in Perfection or my meal at the Chateau Marmont, but AI-generated slop, exaggerated headlines engineered for clicks, and satirical shit-posts.

This is all valid in the context of fashion, as clothes themselves are an identity builder, much like a place. The various fit checks and GRWM, when rendered through an image, dehumanize the self into a commodity. One thing appears like something else, potentially sweet to the eye, when in fact, its reality is unfavourably salty.

Writer and influencer brenda hashtag provides a peak behind the glossy grams of those who attend fashion week, detailing the unseen strain to be invited, maintain a relationship with brands and be pictured front row. She breaks down the whole process, from the invites to the content, but below is a snippet that reveals how sugar is extracted from salt:

“I’m sure by now everyone watching through the screens is aware that these clothes we wear are to be returned the next day. It is a huge honour to be dressed, but there are levels to this shit. If you’re important, you get an in person fitting, with multiple choices that were picked for you, according to your style. If you’re low in the food chain, you’ll get sent grainy pictures of some leftovers (anything that the VIPs and million dollar girls didn’t pick) and saying no is not really an option with powerful brands. They are all sample size, which luckily I can fit into (without breathing), but if you can’t, that’s on you…

…Fashion week is an investment and where you’re seated (and with who), affects how you get paid on other jobs. So it is important. Which is why often talents (and others) go to great lengths to make it to the front row. Some just make it to the front row over social media (by cutting out the heads in front of them for the instagram story), while others arrive late to the show on purpose in order to act confused and have the PRs let them sit anywhere because the show is about to start. Why does it matter? Because only the front row gets photographed. Because other people see you sitting there, in the important seats, giving you importance in their minds. And then later on getting you the important jobs. A show’s seating arrangement is a real life hierarchy.”

This all rings true. When I posted that I was invited to The MET’s Superfine: Tailoring Black Style Press Preview, no one saw the five emails over two months it took to secure my seat. No one saw that the invite came in hours before the event1. No one saw that I had to hustle from one end of the city to the museum on a commute that took an hour. People only read my essay and saw my Instagram. The sugar from the salt. And it was pretty fucking sweet ;)

The MET's Superfine, 'Sinners' and the Cost of Living Forever

Six brown bags wait patiently, as if ready to leave, facing the exit corridor in the last section of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Superfine: Tailoring Black Style exhibit. The scene resembles the final vignettes of a vacation, when your luggage lines the door, waiting for you to roll it home. The c…

Although Miu Miu’s thesis fires a warning shot, calling for vigilance in the face of posturing, I’d argue that society no longer cares if something is real or fake. In fact, artificial things have become embraced and platformed. Gen Z swears by ChatGPT, using the artificial intelligence technology for therapy, to act as romantic partners and best friends; a TikTok creator goes viral for posting over twenty videos on her wedding day and later breaks down how she did it through a well-received explainer video; dupes are praised over the original; Kylie Jenner is suddenly heralded as a ‘girls-girl’ for sharing the details of her breast augmentation in the comment section of her Instagram. We are comfortable with construction. We are comfortable with what is produced. We willingly buy into identities regardless of how manufactured they reveal themselves to be. Authenticity is not an afterthought; it’s no longer in the equation.

Perhaps this is why SKIMS, Kim Kardashian’s shapewear brand, has always fascinated me. I have always appreciated their approach to marketing and their ability to partner with talent with cult followings from Lana Del Rey, Charli xcx, and the boys of Throwing Fits. But beyond their collaborations, I struggled to define what their unique selling proposition was.

And then, with the introduction of the genius pierced nipple push-up bra, a successor to the brand’s nipple push-up bra, I understood. They are selling salt as sugar. SKIMS persists of selling a vision of sex, the proximity to the act without actually engaging in it. It’s a hard nipple over a soft one. A waist trainer over a flat ass. A nipple ring imprint when there is not one there. Soon, I’d expect SKIMS to produce bulge-boxers for men fashioned with dickprints.

SKIMS satisfies our need to transform without actually committing. To post pictures of realities we aren’t living or to assume identities of places we’ve only briefly inhabited. The fantasy is more compelling to try on than actually being ‘bout that life. We try something on and then we move on to the next thing. I had been doing that my whole life.

After trying on Los Angeles, I boarded my flight and moved on to the next thing – home. I look at the picture from that breakfast at the Chateau Marmont, perfectly capturing the delicious croissant and the hot chocolate. But I remember that most LA part of the meal, the green juice, tasted like shit. It was tart, briny, and watered down, reminding me of algae. Next time, I think stick to the Hailey Bieber smoothie at Erewhon. Until then, my bodega in New York makes a pretty solid dupe.

LOOSEY is a biweekly newsletter about culture, art, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

but let me tell you, i had my outfit laid out the night before like it was the day before the first day of school, ready and manifesting that i was getting that invite. and guess what? *anne hathaway voice*… it came true.

I loved this essay, especially the part where you touched on society's acceptance of performance and imagery, and how we all see construction of the self as a norm. Suddenly, authenticity isn't needed anymore, just transparency about our performance is apparently enough. We've found a loophole where people can get away with lying blatantly, as long as they say so; where we can fold to societal pressures and uphold standards as long as we admit that it doesn't come natural to us. Much to think about. Keep up the great work, man, this is real stuff you're doing here.

I grew up moving around frequently, at most I've lived in one house for 4 years before something happened that necessitated us to move. Now I'm in the military, and the pattern continues. I get an ache to move after a while.

Places eventually start to feel stale. Perhaps it's because my locales have been smaller towns, a large part of the discomfort of remaining in one place is the sense that too many people know me.

It may be shame, then. For all the mistakes and wrongdoings I've made, and if I can leave, I can leave it in the past and never have to think about it again. On to fresh new relationships! But I definitely am tired of that cycle.

Thank you for writing about another aspect of frequent moving that I've felt deep down but have never consciously thought about.