The Best Books of The Year

or... the thirty-nine books i read this year 📚

When I think about the art I have encountered this year – be it a film in the movie theatre or a new song – I remember not only the virginal thrill of experiencing something for the first time, but also the place and mindset I was in. When I think about hearing FKA twigs’s ‘Sticky’ on the day of its release, I remember my rain-soaked socks in London; how the movie theatres in Covent Garden were showing films of the late David Lynch as the sky shed tears; how I found my face again and again in the glossy oil paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at the Corvi-Mora; how at dinner I coincidentally met the gratefully stunned Brady Corbet and Daniel Blumberg at Brat restaurant on the night of their respective Oscar nominations; and how finally, I sprawled in the hotel bed later that night, bare belly to a crisp white duvet, cradling a voice note from someone who had travelled to Los Angeles at the tail end of the California fires. Overheated from the wall adapter, my cellphone burned hot in my hand. If I sniffed hard, I could convince myself that I could smell the smoke from California all the way in London.

All these memories are linked. Their sights connected to sounds, smells, and touches. Narratives within narratives. Stories wrapped with stories.

Reading is no different for me. As I scan through the list of books read, I remember the version of me who read each book, and how he changed with each page. I remember what I believed at the time, and what I didn’t know yet. I finished one book and began another, my own story still wet ink on the page.

I read thirty-nine books this year1. I am not the fastest reader, so I have to be picky about what I read next. What I read comes from the non-scientific calculus of bookseller recommendations, literary reviews, and word of mouth from trusted voices. Because of this discernment, most of what I read this year has been exceptional. I wanted to share the list with you.

You’ll find the list is tilted towards contemporary literary fiction, as that was what was on my mind as I worked across fiction projects (one of them being my novella, which you can start reading here). Still, the range is vast, featuring a mix of translated works, buzzy debuts from promising authors, and classics from literary juggernauts from around the world. From the list of thirty-nine, I have to say only two or three were terrible, but you’ll have to guess which ones.

In retrospect, I think I read too much contemporary fiction. Next year, I want to read more classics and straight-up bangers that have stood the test of time. Let me know if you have any suggestions. The eighteen that left a mark on me, and therefore the best, I have expanded into a mini review below the list. Be warned, there’s a lot of glazing, and this post is long, so you might have to read it in a browser if it gets cut off in your inbox. Without any further ado, the Books of the Year, aka the books from any year that I read this year, in order of date read:

Speedboat by Renata Adler (USA)

Evenings and Weekends by Oisín McKenna (Ireland)

Trust by Domenico Starnone (Italy, translated by Jhumpa Lahiri)

The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde (England)

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Germany)

Universality by Natasha Brown (England)

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk (Poland, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones)

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (USA)

Ugliness by Moshtari Hilal (Germany, translated by Elisabeth Lauffer)

Audition by Katie Kitamura (USA)

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp (USA)

Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious by Ross Douthat (USA)

McGlue by Ottessa Moshfegh (USA)

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico (Italy, translated by Sophie Hughes)

Great Black Hope by Rob Franklin (USA)

Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh (USA)

Metzengerstein by Edgar Allan Poe (USA)

Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica (Argentina, translated by Sarah Moses)

Mean Boys: A Personal History by Geoffrey Mak (USA)

Flesh by David Szalay (Canada/Hungary)

Herculine by Grace Byron (USA)

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson (USA)

The Trees by Percival Everett (USA)

Anyone’s Ghost by August Thompson (USA)

The Coin by Yasmin Zaher (Palestine)

The Women by Hilton Als (USA)

The Vegetarian by Han Kang (South Korea, translated by Deborah Smith)

Dominion by Addie E. Kitchens (USA)

Happy Hour by Marlowe Granados (Canada)

The Ten Year Affair by Erin Somers (USA)

Useful Not True: whatever works for you by Derek Sivers (USA)

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor (USA)

Fantasian by Larissa Pham (USA)

Palaver by Bryan Washington (USA)

Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harol Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry by Leanne Shapton (Canada)

Blackouts by Justin Torres (USA)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (USA)

Submission by Michel Houellebecq (France, translated by Lorin Stein)

Heated Rivalry by Rachel Reid (Canada)

📚 Universality by Natasha Brown

Can words ever be neutral? Universality investigates the hidden power of words; their merit, and their biases; whose life is established by them, and whose future is simultaneously undone.

In a work of innovative form, the novel begins with a published article detailing the events that preceded and followed an illegal rave in COVID-era Britain, where one of the partygoers is viciously pummeled with a brick of gold by another attendee.

What comes next is a sequence of meticulously interwoven interstitials, shifting perspectives to bring to life those involved and impacted by the published piece. Each new section reveals varying degrees of information asymmetry, characterizing the novel’s cast beyond the initial article to leave the reader with their own understanding of events.

Early in the inciting article, the crime is introduced as ‘a modern parable’ that exposes ‘the fraying fabric of British society, worn thin by late capitalism’s relentless abrasion.’ This may as well be a logline for the novel as a whole as its narrative cuts across the maddening discourse of the contemporary – the class vs. race debate, the decline of legacy media, and the rise of rage-bait free-thought extremists, the right’s obsession with eugenics, and dismissal of systemic racism, the credit crunch and, ultimately, the great universal unifier, Love Island.

Brown is an expert at developing characters with agility, only to re-characterize them again with a new set of words and an altered perspective that the reader will measure them by. Although her characters’ motivations all point in the same direction – north, towards power – the thorny systems they navigate are unique.

Universality is a follow-up to Brown’s Assembly, an outstanding debut that inspects that relationship between colonial legacy, British identity, and capitalism in a thrilling novella. It reminds me of Industry, and that makes sense; Brown spent ten years in financial services before pursuing writing full-time. I read Universality at my friend Mikey Friedman’s PAGE BREAK reading retreat (where we were able to interview Brown!), and I had the opportunity to review it for THE WHITNEY REVIEW OF NEW WRITING (shoutout Whitney Mallett!).

📚 Stag Dance by Torrey Peters

Stag Dance is not only one of the best written books of the year, but also the most unique. Consisting of a novella and three short stories, Peters, the author of the critically acclaimed Detransition, Baby, migrates across genres to distort and interrogate the boundaries of gender and sexuality in her latest work. As I moved from story to story, I found myself in awe at the range in voice and style achieved by Peters. It felt as though each story (which I believe were collectively written over the span of ten years) was penned by a different person.

In one of my favourites, “The Chaser,” we encounter a first-person dark academia thriller where a boarding student wrestles with his desire for a feminine student that results in violence and brutality. In “Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones,” Peters delivers a dystopian sci-fi where a bio-engineered virus wipes out all of humanity’s ability to produce estrogen and testosterone, effectively making everyone dependent on gender affirming hormones.

But it is in the novella, “Stag Dance,” where the author’s prose and creativity truly transcend. Written in an authentic lumberjack dialect, the story follows the strong, burly, and brutishly ugly Babe Bunyan, an axeman for a logging operation in the 19th-century American West. Despite his masculine figure and his reputation for felling the largest trees, Babe harbors a desire to be seen as soft and meek. Tradwife teas. Because these men are starved for social interaction in the woods without women, the camp boss, Daglish, decides to hold a “stag dance,” in which a man can wear a burlap triangle over his groin to signal that he wants to be courted like a lady and danced with for the night. Tension rises, and chaos ensues while Peters holds firm to a transportive lumberjack diction that feels both otherworldly and hilarious. The novella dares to ask: if your DL trade wanted to be treated like a demon twink for a night, would you indulge? Torrey Peters, come get your baddie chain!

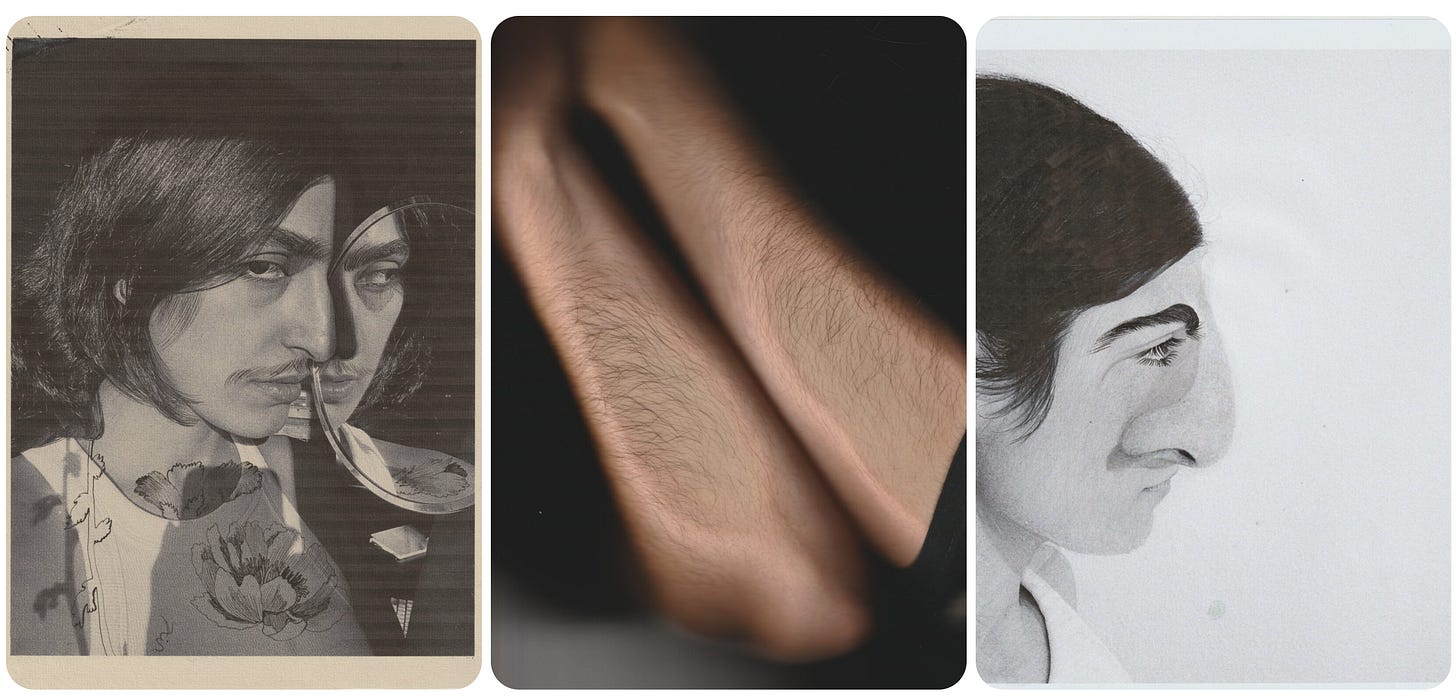

📚 Ugliness by Moshtari Hilal

Afghan-German visual artist and writer Moshtari Hilal examines the political scaffolding that constructs our contemporary understanding of “ugliness” in her outstanding hybrid creative nonfiction project, Ugliness (Hässlichkeit). Hilal begins with herself as a foundation before going outwards; she uses her dark skin, the hair on her arms and upper lip, her long nose, and other features natural to Afghan women to investigate the violence of beauty ideals and how these “standards” have been used to justify hatred. With lyrical prose, Hilal cycles through eugenics, the history of rhinoplasty, Kim Kardashian and “Instagram face,” AI surveillance, body fascism, digital performance, and the impacts of colonialism to conclude that “ugliness” is not a neutral observation, but an inherited system of hatred based on centuries of white supremacy. Although her conclusion isn’t shocking, the story she weaves is extraordinary.

On a rainy Wednesday in March, I went to The New School in Manhattan to witness Hilal in conversation with New York Times columnist and Hofstra University literature professor rhonda garelick about the forces of ugliness. Hilal spoke with surgical distance about confronting the “project of ugliness” through her self-portraits and her experience as a teenager in Germany. She spoke of how the project of beauty is really just assimilation – a negotiation and erosion of the self to get closer to a “standard.” Her art, as well as her personal history, is well-paced throughout the book, splicing her essays and lyrical verses with confronting visual vignettes.

I had not heard of Moshtari Hilal prior to encountering this book, but after hearing her speak, I left with the feeling that she is going to be one of the most important artists of our generation. Upon finishing the book, I found myself questioning the idea of a physical “type,” and whether interest in a romantic partner is something that can be molded, or if that, too, is inherited from decades of propaganda. How much of this, for those who are willing, can be deprogrammed? Can attraction be an acquired taste, earned like an appreciation for great art? And does knowing all of this – that from the moment you were born you were taught who to love and who to hate – make you more empathetic, or more angry?

I don’t know, but I hope Moshtari Hilal will tell.

📚 The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde once described The Importance of Being Earnest as “exquisitely trivial, a delicate bubble of fancy, and it has its philosophy: that we should treat all the trivial things of life very seriously, and all the serious things of life with sincere and studied triviality.” This is the energy I wish to be taking with me into 2026. Riddled with clever wordplay and the absurd convergence of comically tense situations that feel ripe for a Safdie film, Wilde’s final stage project still reads refreshingly contemporary. I saw the new play production in London’s West End with Ncuti Gatwa, and I’m praying they bring it to New York.

📚 Audition by Katie Kitamura

Utterly beguiling with a stylish yet economic use of language, Audition was one of the books I thought of the most this year. Kitamura is a master, a chief architect of sentences, but simultaneously apt at curating a ‘vibe’ beyond the novel’s words and narration.

Without giving away too much, Audition is split between two acts, both of which a woman – an actress – sits across from a younger man. On Page 38 of the hardcover, Kitamura’s narrator says, “There are always two stores taking place at once, the narrative inside the play and the narrative around it, and the boundary between the two is more porous than you might think.” Not only is this relatable to this newsletter’s thesis at large, but it is also useful for interpreting the novel, because yes, this is a novel that leaves the reader to come to their own conclusions.

I finished the novel in my hotel room in São Paulo and immediately felt the need to discuss its special ending. I am curious to see how it will be adapted, but excited nonetheless. Special thanks to Hunter Harris for getting me on the Kitamura train with Intimacies. I must read A Separation next.

📚 Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico

Earlier this year, I wrote about my imaginary move to Los Angeles, breakfast at the Chateau Marmont, the discourse around New York’s ‘West Village Girl,’ the SKIMS nipple piercing push up bra, and Miu Miu’s Spring Summer Collection in a popular essay called “Sugar Looks Like Salt,” all tying back to the constructed identity and it’s relaton to place. At the heart of this essay was a review of the now much-celebrated book Perfection.

Within its pages, we follow Tom and Anna, a twenty-something-year-old expat couple who live in Berlin. The novel’s subjects are familiar but opaque, rendered in such a way that we understand that they are people as much as they are symbols for the ‘millennial creative professional.’ Their hollow characterization – unsupported by dialogue, as there is none in the novel – allows us to project ourselves, and those we know, onto them. We understand that Tom and Anna come from a specific part of Europe, but the novel’s stencilization of them lets us know that they could have come from anywhere. They are skeletons, and we are the flesh. Even though the novel occurs in the mid-2010s, part of its success is that it feels applicable to the post-pandemic remote work and ‘digital nomads’ of today.

Throughout the novel, the couple’s life and career persist through images on social media – the creative assets they design for clients that exaggerate the appeal of the brands that pay them, but also the performance of their own identity and expat lifestyle on their personal Instagram pages. The main character of their digital portraiture is not just them, but specifically them in Berlin, as they absorb the local culture as their own. Throughout the novel, Latronico is sure to emphasize the contrast between the reality of their life and the images they post.

📚 Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh

As a longtime admirer of Ottessa Moshfegh’s novels, I have always been intrigued by the fact that her preferred medium is the short story. Because of this, I picked up Homesick for Another World – published between her debut novel, Eileen, and her most popular work, My Year of Rest and Relaxation – to see if it “hits different” in her preferred literary form. It is always a fruitful voyage to venture back to an artist’s earlier work, especially a writer like Moshfegh who, since the immense success of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, has ushered in a generation of mimics whose contributions have canonized her style into a distinct genre, widening the tent for her followers to publish fiction in a category that is both commercially successful and critically acclaimed. Lowkey what Nicki did for ‘female rap,’ or what Lana did for ‘sad girl pop,’ but that’s for another essay.

I was delighted to find, when reading this “OG” Ottessa, that her themes of alienation, repulsion, and humanity at its most depraved (which is to say, its most human) are still potent. I found the collection similar to my “problematic fave” Flannery O’Connor’s story collection A Good Man Is Hard to Find, in its display of flawed, misguided characters in search of fulfillment while exposing the ugliness of the human soul. I love me some Flannery, even though I don’t think she would have loved herself some me.

In aggregate, the collection points to the spiritual and moral rot of society while remaining stylish and crude on an individual level. My favorite stories were “Slumming,” in which a member of the liberal elite participates in class tourism, summering in a rural, opiate-addicted town to experience something “raw” while looking down on the inhabitants; and “Beach Boy,” where a recently widowed man travels to an island resort to find the “beach boy” with whom his late wife had an affair. These stories feel like a perfect fit for Yorgos Lanthimos’s Kinds of Kindness, which makes sense given that he holds the production rights to My Year of Rest and Relaxation. I’m seated for whatever comes next, but will probably read Death In Her Hands next year, the only Moshfegh I’ve never read.

📚 Mean Boys: A Personal History by Geoffrey Mak

In a striking blend of criticism and memoir, Geoffrey Mak’s Mean Boys examines the culture wars of the 2010s and the art scene of New York and Berlin against the author’s own sexual and religious reckoning. Mak’s ‘mean boy’ is the archetype of a trendy hypebeast, known for his proximity to subcultures and his uncanny ability to link the underground to commercialization through participation in clout wars and exposure. Chances are that Mak’s ‘mean boy’ would have read LOOSEY.

I much preferred Mak’s cultural writing over some of the other essay collections that try to dissect this era because you can tell that he was, as Lil’ Kim once said, actually “in the cut like a Bandaid.” Mak’s active participation in the era made his observations more powerful, and their impact, both good and bad, as the memoir reveals, more realized. Reading this debut reminded me of one of my favourite books from last year, Mercury Retrograde by Emily Segal of the K-HOLE trend forecasting collective. It’s a golden era for New York that is already becoming nostalgic bait for Gen Z. I suggest you read them in duet.

📚 Flesh by David Szalay

To frame this masterpiece as the “detached male, but daddy maybe I CAN’T fix him” novel of the decade would be reductive but true. The Dua Lipa-anointed, Booker Prize-winning Flesh follows the life of István from adolescence to adulthood as he attempts to make sense of his role in society. Strangled under the terse boot of masculinity and simultaneously exploited and empowered by his role in the patriarchy, Flesh interrogates the double-bind of manhood.

I found myself intrigued by the novel’s exploration of geography: how István’s Hungarian heritage and humble housing estate beginnings became more erased as he assimilated into London to become a part of the British elite. As he descends into Western Europe, he continues to trade on his masculinity until he is completely spent. Although Szalay maintains distance from his emotionally detached protagonist, the space in between – the restraint shown by the author – allows the reader to fill in the cracks with empathy. This is an extremely hard thing for a novelist to master: to trust the reader to fill in the gaps rather than telling them yourself.

📚 Herculine by Grace Byron

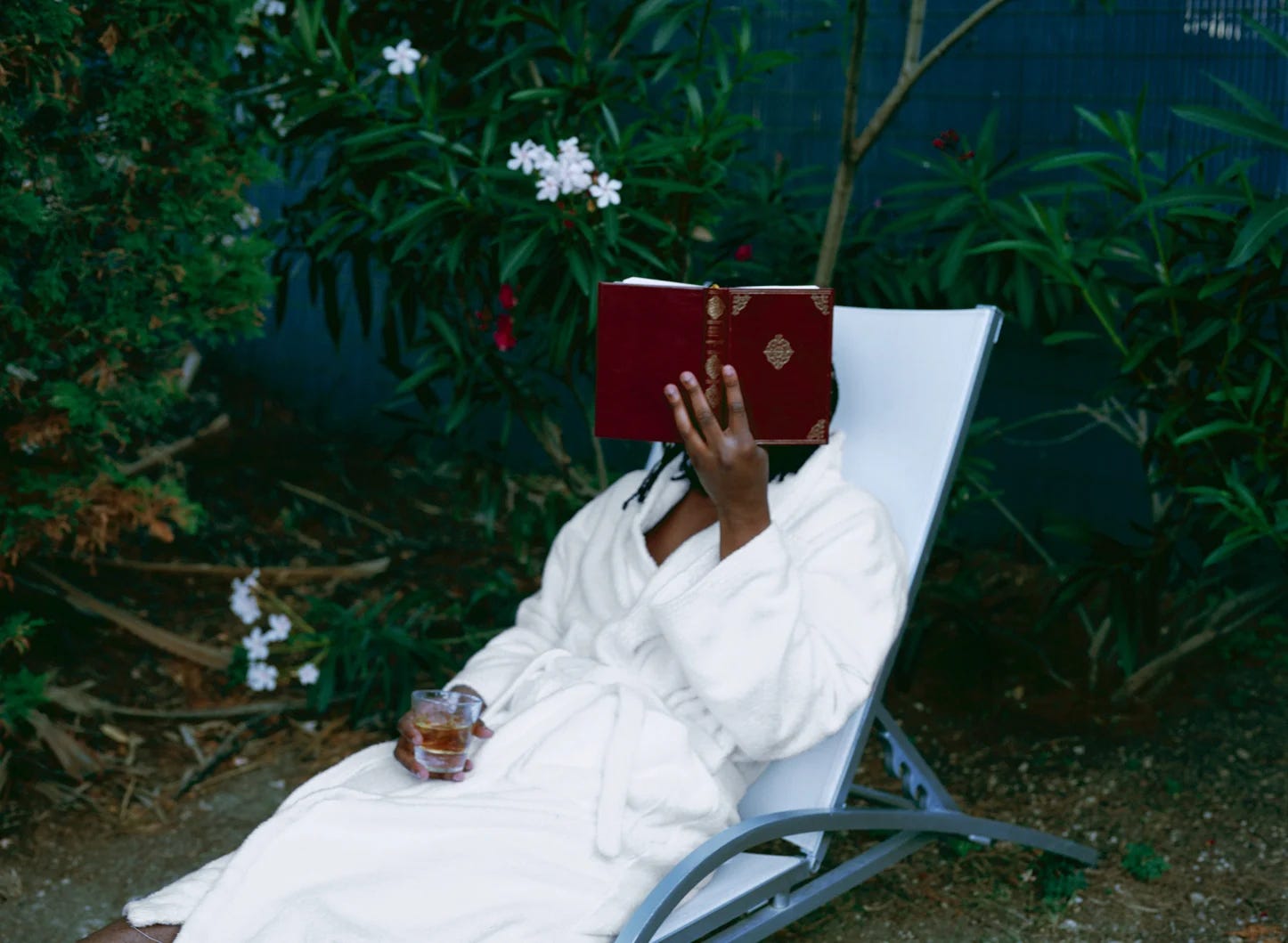

I had the pleasure of reviewing Grace Byron’s debut for THE WHITNEY REVIEW OF NEW WRITING and engulfed the proof her publicist provided to me on the rocky beaches of Marseille late this summer.

In Herculine, the unnamed narrator finds herself out of a job in New York and lured to a trans commune in Indiana by her ex-girlfriend, Ash. The commune, named Herculine after French memoirist Herculine Barbin, is pitched as an idyllic refuge from the nihilistic, hetero-capitalistic New York, but this turns out to be a mirage; things never look as good as the postcard, do they? In a delightful fusion of literary fiction and gothic horror, Byron’s debut examines how the past continues to creep up and interfere with the present, through the narrator’s reveries of psychological trauma from conversion therapy to the spiritual malady stemming from the literal satanic demons that stalk and follow her.

Although a work of fiction, Byron’s expansive literary talents are on display, specifically her acute knack for cultural criticism in her observations of New York, the bleak state of modern writing, and the power dynamics within the trans community. Often, her commentary is delicious snark, like the titles of the articles “Hot Freelance Girls” write – I Know My Sister Is Ugly, and Ernest Hemingway Was a Trans Woman, Prove Me Wrong. What this establishes is a horror story with two haunted houses: the hopeless New York that the protagonist flees from, but also the eerie commune that functions more like a cult. Soon, you start to wonder if the narrator can truly outrun herself, and if so, where will she go?

📚 The Trees by Percival Everett

Earlier this year, when I was in Paris, I received a text asking me if I was available to write an essay on The Trees and Emmett Till for Dua Lipa’s book club. I had ten days to read the book, to conduct extra research on Till’s murder, and interview folks from the American South, as well as an eight-hour flight home, before the draft was due. I’m glad I accepted.

The Trees takes the brutal lynching of Emmett Till and situates it in an investigative satire, where two state detectives collaborate with local sheriffs to unpack a mysterious series of deaths in Money, Mississippi, where the brutalized body of a boy – who resembles Till – momentarily appears next to the bodies found. It’s dark, surreal, and cheeky.

The longest chapter of The Trees is perhaps the most harrowing. In it, a historian archives the names of over six thousand Americans who have died from being lynched. He writes out each name by hand, saying, “When I write the names, they become real again. It’s almost like they get a few more seconds.” I wrote about this archiving, amoung other things, in this newsletter.

You can read my essay on The Trees and Emmett Till for Dua Lipa’s book club here.

📚 Anyone’s Ghost by August Thompson

Do you ever just yearn? Anyone’s Ghost is a coming-of-age story divided by three car crashes that spans rural New Hampshire and New York City, telling the tender story of blossoming friendship, strained love, and, ultimately, loss. The relationship between the narrator, Theron David Alden, and his friend Jake is so well articulated by Thompson – with such beautiful prose – that it feels like a sucker punch. It’s devastating but familiar, wrought with the meek hope of doomed love. My paperback is full of tagged pages and underlined sentences, but the passage below shows you just how effective Thompson is at evoking the dizzying haze of romantic validation from a long-awaited crush.

Every hundred feet, we stopped, and one of us would pull the other in, sometimes kind, and kiss again. I like to think we radiated, that the few strangers walking past were moved by our excitement. That they also knew we were getting away with something each of us once thought was impossible… The reality was that we probably looked swaying and unkempt and even a little crass. Pawing at each other, testing the other’s limit. But mainly, I think we looked boring. Another set of drunken boys on their way to a run-down, cliche apartment. An average Manhattan tussle that felt, from the inside looking out, like the only true thing ever created.

This debut is a certified banger. Shoutout to Tell the Bees for recommending it. Pair this with Xavier Dolan’s Matthias & Maxime for a good time.

📚 The Coin by Yasmin Zaher

On a flight to California, I finished reading The Coin by Yasmin Zaher, a debut novel that follows a Palestinian woman who moves to New York and becomes an elementary school teacher for underprivileged boys. Throughout the novel, she unravels. She cleans herself obsessively for hours a day, becomes involved in an international Birken-selling scam with her (maybe) homeless (maybe) boyfriend, and maintains a bizarre teaching method with her students.

The novel is told through short, first-person splices that cut between her past and present. Early on, we learn that she is haunted by a childhood memory of accidentally swallowing a coin on the day of her parents’ death. She then inherits a great deal of wealth from their will. However, upon moving to New York, she feels as though that coin, still lodged inside her, has begun to spin.

This book made me think a lot about generational inheritance, colonialism, and the stain of capitalism. How our ancestors pass down their suffering to us. It’s very “I guess the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree” coded. I wrote about it here. Shoutout to Leah Abrams for recommending this to me. The following passage is my favourite from the novel:

I thought about metal then, and the landscape of my childhood, how it was saturated with coins. Roman coins, gold Abbasid coins, ancient Judean coins. There were shekels, mils, and drachmas. Emperors, gods, and queens. They didn’t decompose. They just stayed there, in the ground. And the coin in my body, it was going to stay there until I died, and long after.

📚 The Vegetarian by Han Kang

With the sublime perversion and violence of a Michael Haneke film, The Vegetarian is a work of high literary art – a triptych of perspectives that shows the dismantling of a woman’s life (a wife, a sister, a muse) due to her abrupt decision to stop eating meat. The novel, which takes place in South Korea, investigates the relationship between sanity, conformity, and patriarchal oppression. Beyond the narrative, which at times feels surreal, what will remain with me are the dreamlike images rendered by Kang, the vivid implications, and the exploits of the titular vegetarian. Huge thank you to Nic Marna who moved me to read this book from his “Year With Han Kang” series.

📚 Happy Hour by Marlowe Granados

Reading this book made me really happy and optimistic about life. I don’t know why it took me so long to pick it up, but I am glad I saved it for this particular moment. Happy Hour is resident literary showgirl Marlowe Granados’s buoyant debut, a story told in diary entries that illustrate the romp of two women in their early twenties who take on New York under suspicious immigrant statuses and get into all the trouble but have all the fun. Although Isa’s confident narration is rich coming from a twenty-one-year-old, I found her remarks and observations not only moving but sharp and applicable. Here is one, for example, that appears early on in the novel:

“If I were to describe typical New York conversation, it would be two people waiting for their turn to talk.”

But one of my favourite passages that I read all year lies on page 152 of the Verso Fiction paperback edition. Here lies the magic of Happy Hour, the overlooked resilience of a party girl who must marry her pursuit of fantasy with the realities of what is before her. On this page, Isa has come to terms with the fact that her lover has not lived up to her expectations of him in her head:

He said, “What do you want?” All I could think of was peeling the skin of a Valencia orange in bed on a bright morning with someone pulling me into the cover because they want to spend two or three minutes nestling before starting the day. So I said, “ Not much.”

I quickly concluded that I was sick of being there. “I’m leaving. I like to leave first… You’re a stranger to me. I can’t even remember your face.” People forget that I can be cruel sometimes. I can devastate just about anyone.

A party girl’s best trick is knowing just when to leave. Marlowe Granados and I have not met yet, but, as a fellow Canadian, I am certain our paths will cross sooner or later. Our vesper martini glasses are fated to clink. Her much-awaited follow-up, Petty Intrigues, was announced earlier this year.

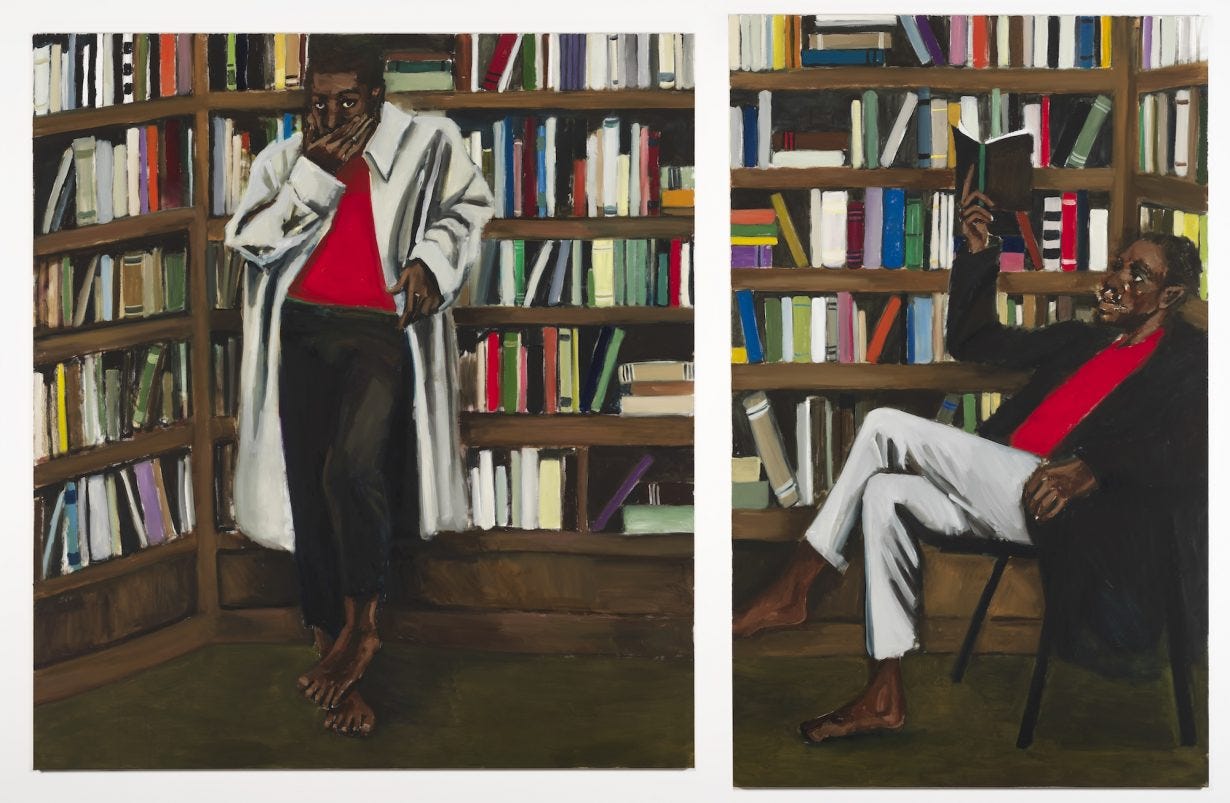

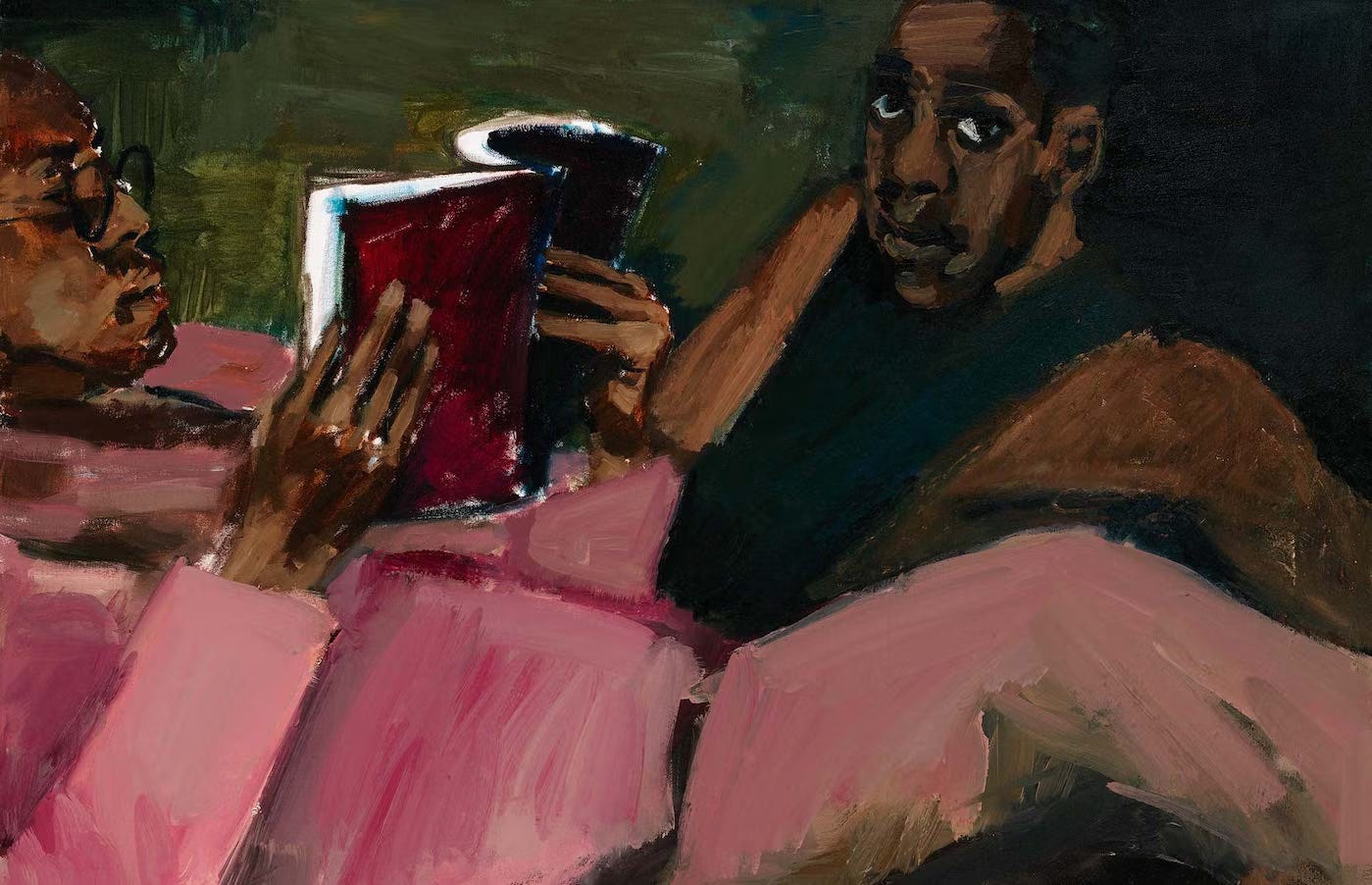

📚 Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor

When I was in São Paulo, I was invited to the São Paulo Museum of Art for a tour and dinner. On one of the floors, there was a room with hundreds of artworks, and instead of being attached to a wall, they were displayed on freestanding poles that let you see the front and back of each canvas. This setup allowed you to first focus on the art itself, then mosey around to see who made it and where they were from, as the information was withheld on the back. It was a powerful way to evaluate the work without the bias of the artist’s biography.

In Minor Black Figures, we meet Wyeth, a painter frustrated by the art world’s tendency to link the race of Black artists with their work, often misrepresenting their focus. At the core of the novel is a romance between Wyeth and an ex-priest, with really hot sex scenes, and lush descriptions of New York and the people who live in it. What I found striking was how Taylor, much like the museum in São Paulo, withheld the race of certain characters, sometimes revealing it and othertimes not, which challenged my own biases as a reader. I kept thinking, “Well, what is the race of this person?” and then questioned that impulse and how it related to the book’s overall message. It isn’t until much later in the book that the specifics of Wyeth’s origin are revealed, in a detail so subtle I had to read it multiple times. I was gagged and thought it was brilliant, and when I called a friend who was reading it, he told me he missed it and was gagged, too. That shifted how I interpreted the character’s behavior, but should it have? I guess that’s part of the genius of this novel. I will learn more when I read Taylor’s interview with Lincoln Michel.

I have read all of Brandon Taylor’s novels, and this is my favourite. He also has a great newsletter, sweater weather.

📚 Fantasian by Larissa Pham

I have been a fan of Larissa Pham’s writing since her debut essay collection, Pop Song. I had always known that she wrote an erotic novella, Fantasian, but, after trying to buy it years ago, I discovered that it was no longer in print. In a way, there’s something really chic and sacred about this, especially for erotic fiction. The power of print is that there are limited copies, which, as a writer, would make me feel a lot freer than writing on the internet, where the scale is infinite, and words can be copied and pasted outside of their context.

But this summer, I came across Fantasian in a used book store and pounced on it, completely forgetting it was erotica. The novella takes place at Yale, where an Asian student encounters her doppelganger, and the two develop an obsessive fascination with each other. It’s a fever dream at the fork of self-love and all-consuming narcissism. Rich with raunchy motifs of desire, envy, and self-pleasure, I am seated for Pham’s debut novel, Discipline, which is slated for release in a few weeks.

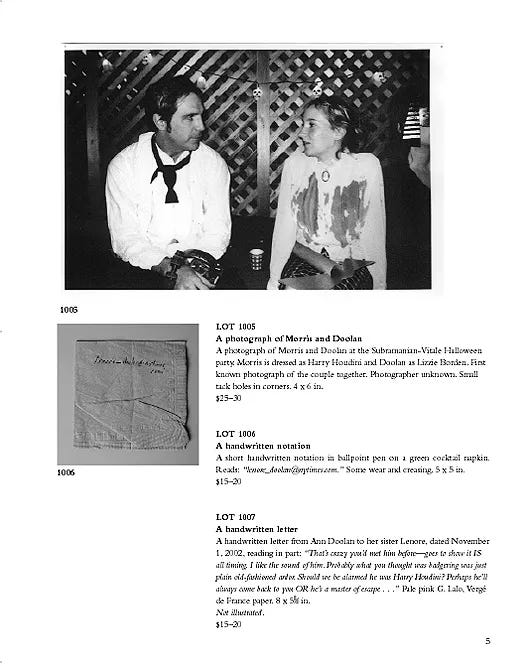

📚 Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry by Leanne Shapton

It’s giving “picture book, but make it arthouse.” In this book, Shapton presents the spark, the duration, and the demise of a fictional couple’s romantic relationship through staged images of their belongings in an auction house. Throughout the pages of the book are editorialized items from the couple: Polaroids from Halloween, receipts from restaurants, gifted pajama sets, movie theater stubs, love notes on hotel notepads, and dog-eared books. Each image is accompanied by a small caption to give context to the item – written in the tone of an auction info sheet – but at times, I preferred to just look at the images and try to make sense of the storyline from those alone.

Although the relationship ends, this creative novel is a delightful reminder that you can get to know someone (and their most important relationships by default) through their possessions. Finally, Sheila Heti poses as the titular Lenore Doolan in the book, which is super cool.

Have you read anything on the list? If so, what did you think? If not, what should I read that you loved?

LOOSEY is a newsletter about culture, art, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

It must pain you that this isn’t a clean fourty. It will be fourty by the end of the year. I’m currently reading The Secret History by Donna Tartt, and I refused to speed-read it for this list, so you’ll just have to accept me flaws and all.

I read The Vegetarian months ago and still randomly think of it. Such a good book!!!

Wait I'm OBSESSED with Important Artifacts and planning on doing another post about it in January! I think about it all the time. So clever, so sad.

We have a lot of overlap for my top books, and yessss at the Anyone's Ghost love! It's so beautiful, genuinely. Clapping for Stag Dance and Universality!