What's the difference between facts and the truth?

dua lipa, percival everett, toni morrison, and me

Dua Lipa’s Service95 team commissioned me to write an essay on Emmett Till to run alongside her book club selection, The Trees by Percival Everett. You can read my piece here. Up until this point, I had never written a profile for a dead person, let alone an American teenager who was lynched on the false claims of whistling at a white woman. But the facts of his story were seared into my consciousness from a young age. I could recite his story with the acuity of the more recent Trayvon Martin; their fatalities mirror – a Black boy walks into a convenience store and ends up dead. I imagine this is similar for many Black people who grow up in the West, Till’s death serving as a perennial warning of how youthful innocence knows no protection from hatred. Facts that haunt like vicious folklore.

Still, the assignment unnerved me. I was anxious, not that I would get the facts of the story incorrect, as there were numerous artifacts for me to dive into – books, articles, films – but that the gruesome details of the story would shine greater than Till’s humanity. Sure, I could put together a laundry list of events, but a list doesn’t make a human. Facts alone do not make a child.

When Emmett Till’s mother decided to have an open casket funeral for her son, she sparked the beginnings of the American Civil Rights Movement. Till’s death became a national spectacle, surfacing as a topic of Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches and mentioned by Rosa Parks when she refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. With the details of his murder acting as lightning rods of attention in their own right – the barbed wire around his throat, the Tallahatchie River his corpse was dumped in, the open casket funeral for the world to witness his bludgeoned face – how could I draw remembrance to the child that was in the casket? How could I honour Till’s humanity beyond the howls of his horror story?

The world has a strange way of answering questions if you’re paying attention. Between being commissioned to write the story and it being published, a friend asked me to participate in a group reading of Toni Morrison’s The Site of Memory at the Museum of Modern Art. The city was wet that evening, the clouds splitting open in a sweaty downpour as we careened from a rushed dinner of larb and roti on 46th Street to the museum on 53rd. Later, on TikTok, I would see videos of subways and side alleys being flooded. I had been out all day, at the movies, out to lunch, and so you are correct to assume that I did not review the text in advance, telling myself that I wanted to save it for the session so I could be ‘surprised.’ Thankfully, no prior reading was necessary, and the session, led by curator Gee Wesley, focused on critical excerpts from Morrison’s essay that we discussed aloud. Almost immediately, I found the topic pertinent to the profile of Emmett Till.

In her text, Morrison argues that there is a difference between fact and truth by establishing a link across successful biographies and fiction. To her, both must honour the human experience beyond its sterile facts:

“The crucial distinction for me is not the difference between fact and fiction, but the distinction between fact and truth. Because facts can exist without human intelligence, but truth cannot. So if I'm looking to find and expose a truth about the interior life of people who didn't write it… Then the approach that's most productive and most trustworthy for me is the recollection that moves from the image to the text. Not from the text to the image.”

Much of Morrison’s work involved ingesting the cold facts of the Black experience and threading them into compelling portraits of life beyond their hardships and horrors. For her, this was especially relevant for slave narratives, where the details were sparse and likely not recorded by the subject themselves, and therefore were devoid of the visceral emotion of those who lived that experience. As a result, the facts could omit key truths or misrepresent the humanity of the lives it seeks to catalogue. To remedy this, Morrison brought her pen to the page and wrote. In the essay, she continues:

“If writing is thinking and discovery and selection and order and meaning, it is also awe and reverence and mystery and magic. I suppose I could dispense with the last four if I were not so deadly serious about fidelity to the milieu out of which I write and in which my ancestors actually lived. Infidelity to that milieu - the absence of the interior life, the deliberate excising of it from the records that the slaves themselves told - is precisely the problem in the discourse that proceeded without us. How I gain access to that interior life is what drives me and is the part of this talk which both distinguishes my fiction from autobiographical strategies and which also embraces certain autobiographical strategies. It's a kind of literary archeology: On the basis of some information and a little bit of guess-work you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply. What makes it fiction is the nature of the imaginative act: my reliance on the image - on the remains - in addition to recollection, to yield up a kind of a truth. By ‘image,’ of course, I don't mean ‘symbol’; I simply mean ‘picture’ and the feelings that accompany the picture.”

When I returned to this, my anxiety around the piece molded into something more concrete, more useful: a duty. The apprehension I felt was precisely what Morrison described: her balance of selection and order with reverence and mystery. How do you move someone beyond the facts to provide them with an image of the truth? With Till, I knew I was not writing fiction. To ‘make up’ something about his life would have been inappropriate and not what I was commissioned to do. Yet Morrison’s perspective on ‘reconstructing the world’ as an imaginative act when writing a biography was useful in helping me build beyond the facts to provide readers with an image of a story that is, at the end of the day, about one of the most famous images in American history.

In his interview with Dua Lipa, Everett specifies that the history of lynching is not one of Black history, but one of white America. The Trees is an astounding work of literary fiction and satire that is as challenging as it is clever, unearthing and remolding muddy American history into the unsettling contemporary with a fast-paced, detective mystery. Dua Lipa's introduction to The Trees came in 2022, the year the novel was longlisted for the Booker Prize. She was a special keynote speaker at the award ceremony that year and was immediately captivated by the book's prose. Dua describes the narrative like this:

“The scene: a white man in Money, Mississippi, is brutally killed, and the battered corpse of a long-dead but familiar young Black man is also left at the murder scene. Before long, a second white man is found beaten and mutilated, with the same Black figure by his side. As more and more men wind up killed, each with these eerily similar dead bodies beside them, local cops are left baffled – and mayhem ensues.”

Pretty quickly, the plot flips to subvert TV-show tropes as detectives Ed Morgan and Jim Davis are sent down from ‘the big city’ to aid the local cops in their investigation. Soon, they discover that the recurring Black corpse resembles Emmett Till. As someone who loved True Detective season one, this immediately hit for me. The story is haunted by the spirit of racial reparations, but is equal parts humour and horror. By situating the novel in the familiar landscape of the detective story, Everett disarms us with his satire, the witty dialogue of his ensemble, and the hard truth of America. He evokes precisely what Toni Morrison calls writers to do in The Site of Memory, applying magic to reveal human truths in the space between facts.

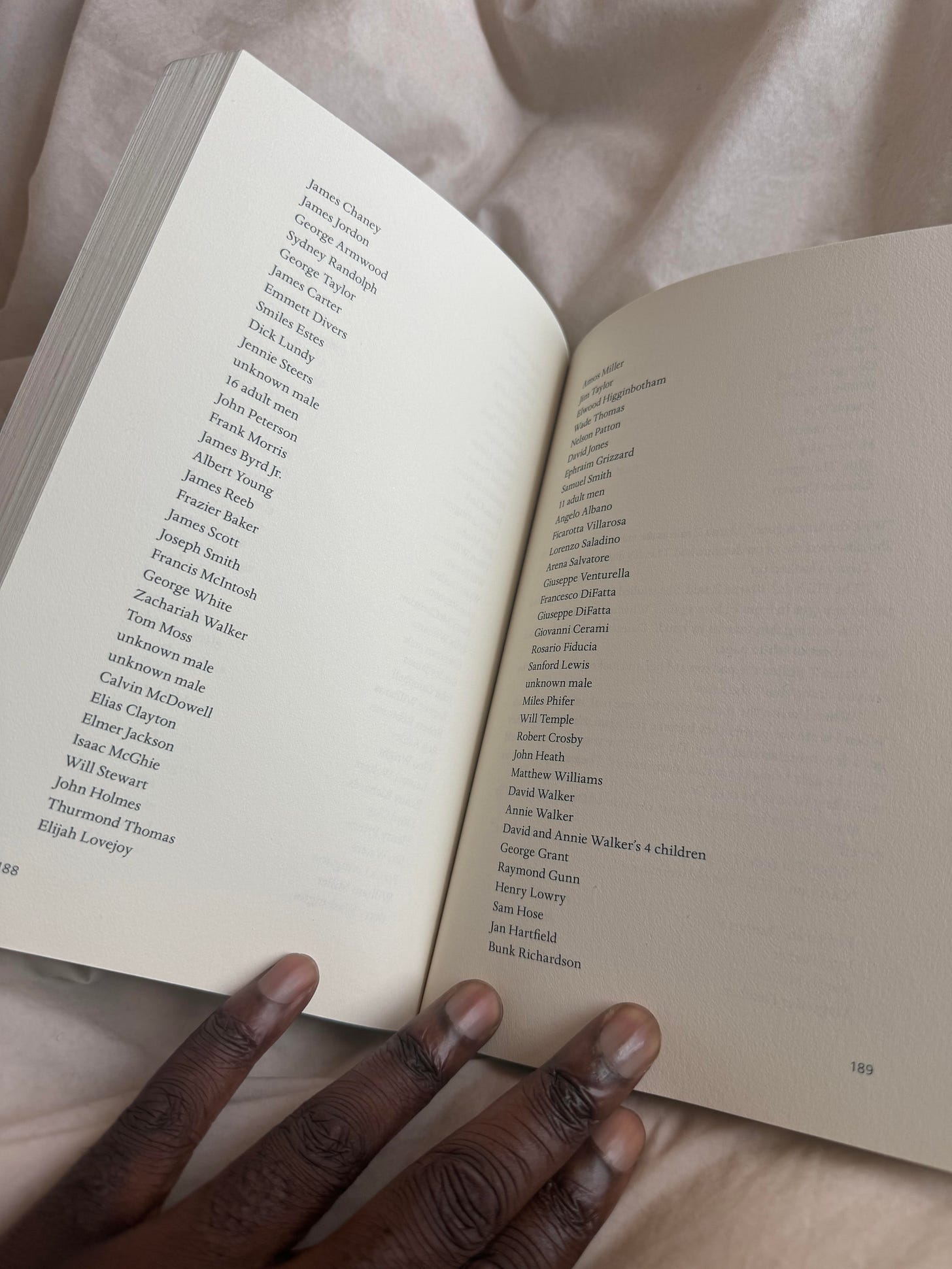

The longest chapter of The Trees is perhaps the most harrowing. In it, a historian archives the names of over six thousand Americans who have died from being lynched. He writes out each name by hand, saying, “When I write the names, they become real again. It’s almost like they get a few more seconds.” An excerpt of the names is provided in the book in the form of a list:

In his interview with Dua Lipa, Everett explains that he wrote the names by hand, too, but as I read the chapter, I realized that the names Everett included were not fictional. The collection of names was of real people, leading into the present with mentions of Eric Garner and Trayvon Martin, but also names of Asian and Native Americans who were also murdered. The most chilling mentions on the list were the ones without names, which simply survived as nouns like unknown female or 16 adult men. Cold facts on a brute page. But this is where the magic that Morrison writes about comes in: by writing them down and putting them in fiction, the world provided an answer. During the first printing of The Trees, a reader from Tennessee reached out to Everett to provide him names of a lynched family – originally listed as David Walker, David Walker’s wife, and David Walker’s four children. With the reader’s help, Everett updated the respective unknown names to the actual names for future editions, moving the mere facts to something more human: a truth. “Now, when I do the reading, I say David Walker, Annie Walker, David and Annie Walker’s four children,” says Everett. “I would never have learned that, it would never have meant anything to me, if I hadn’t written about it. And that changed my life.” By writing the names, they become real again, is what Everett’s character said, but perhaps that was a prophecy for himself, for writers. Earlier this year, Everett went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for James, 37 years after Toni Morrison.

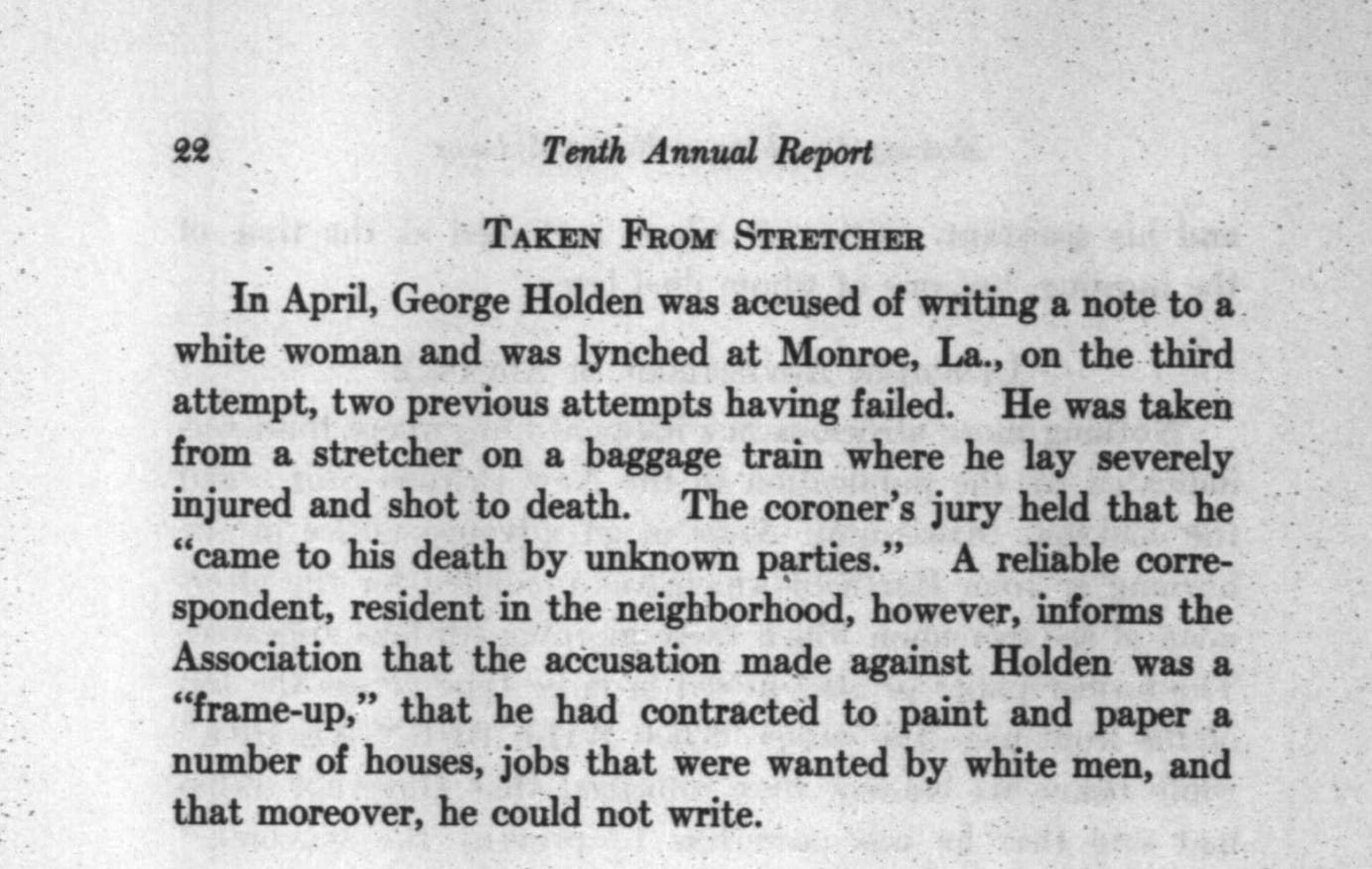

I read the names with interest until I was held by a name that looked familiar: George Holden. The surname was eerily similar to mine, and so naturally, I looked the name up. The reports indicate that his lineage hopscotched back and forth between the names Holder to Holden interchangeably, but most of his family tree maintains the latter. The prospect of being related to him went against everything I knew about my family history. My family hails from the Caribbean, and as far as I know, I am the first from my family tree to immigrate to America. Still, I studied the facts of George Holden’s life, mystified by the chance of a bizarre relation. I studied hospital reports and government documents, but the details were sparse. What I know is that George Holden was lynched by a mob of white men in 1919 on the claim of writing a note to a white woman in Louisiana. This was the mob’s third attempt to lynch him, following an attempt at a hospital in Monroe, Louisiana, where the nurses successfully protected him. Eventually, the mob found him on a train the next day and lynched him in the baggage car. I don’t know how old George was. I don’t know the contents of the letter. All I have is this report that suggests that, like Emmett, George was falsely accused; that he could not even write. And so, for him, I must.

I began my profile of Emmett Till with a vision of the Mississippi River. I researched tributaries to understand the waterways of America and interviewed folks from the South who grew up along the rivers it splits into. The river is a constant motif in my essay, representing where Emmett’s corpse is found but also the legacy of violence that pulses through this country like a vein:

“The Tallahatchie River runs brown like skin, bending in the basin of a horseshoe, picking up sediments of silt and clay before draining into the Yalobusha River. The north pigtail of the Yalobusha slices across Money Road before meeting the south tail, imprisoning the southern town of Greenwood in the bird’s-eye view of its noose. There you’ll find the usual things you’d expect to find in a town: a Walgreens, a Bed, Bath & Beyond, and a church that overlooks the Tallahatchie, 13 miles from Money, Mississippi. The Yalobusha River continues on, meandering southwest and eventually bleeding into the Yazoo River, carrying more soil to muddy its complexion before eventually flowing into the Mississippi River, the second-longest river in the United States of America.

In 1955, when Emmett Till’s body – five foot four and bludgeoned beyond recognition – was dumped into the Tallahatchie, he never made it to the Mississippi. Instead, he sank, his lifeless body weighed down by a 75-pound fan looped around his throat with barbed wire, plummeting him into the river’s mahogany streams. Silently, he drifted there, camouflaged for three days while his family and the local authorities searched for him. On the third day, his body began to float to the surface, naked and mutilated, soon to be discovered by two teenage boys who had stuck their rods in the river to fish. When he was retrieved from the water, he was unrecognisable; so pummelled beyond comprehension that only his mother could identify him.”

I was surprised to see that Morrison had written about the Mississippi, too, in her essay. For her, the motif of flooding represents the process of invention that moves fact closer to the truth. Here she writes:

“Because, no matter how ‘fictional’ the account of these writers, or how much it was a product of invention, the act of imagination is bound up with memory. You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally, the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact, it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, what valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there, and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory – what the nerves and the skin remember, as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our ‘flooding.’"

It's uncanny, these bizarre linkages across texts and time that ultimately stretch towards the same truth. The story of Till, of Holden, of Martin, of everyone on that long, long list. As I edit this, a storm rolls through New York, and the flooding is what my mind returns to. The rain fills in the gaps. The overwhelming rush of emotion that licks an arid landscape. And then, the water — the tears — remembering what it still is.

My serialized novella ‘Come If You Want’ has arrived. Read the first chapter here:

Come If You Want - Chapter One

You are reading ‘Come If You Want,’ a serialized novella by Brendon Holder. This is the first of four chapters.

Read more LOOSEY…

The Big Business of Being Cancelled

We’ve been here long enough to know that being ‘cancelled’ is temporary. The typical cancellation cycle yields a surge of attention, bolstered by press and social media take-downs, and, at its apex, results in a loss of work that is almost always superficial while never bordering on true financial risk. The cancelled individual…

In search of the perfect t-shirt and taste

I love Paris the way that only someone who doesn’t live there can: with the rose-tinted glaze of a vacation fling that you never commit to, unbothered by its impracticalities.

LOOSEY is a newsletter about culture, art, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

Thank you for bringing us into your writing process in this way, and for this study. Separately, I recently learned that there were groups of ppl enslaved in the states who later ended up in the Caribbean (some were loyalists to the Brits and fought for them in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812). So relation to Mr. Holden is not impossible!

this was beautiful. can't wait to read the essay. <3 Morrison is always so essential and so cutting and pure in all of her assessments. What an honor.