Would you rather be hot online or in person?

"fall is approaching, the body can’t save y’all anymore, face card gotta eat!"

In the final gasps of summer, I encountered a tweet that read like a prophetic warning: Fall is approaching, the body can’t save y’all anymore, face gotta eat!

The implication was that as the warm summer months of muscle shirts and crop tops ended, a person could no longer rely on a conventionally attractive body to gain the attention they desired; instead, they had to rely on their face. The tweet sparked like flint, chewing through the feeds of the internet with every repost, surfacing in group chats and spawning a frenzy of takes on whether it was legitimate or false, problematic or not.

Although I don’t know the Twitter user personally, I detected something moralistic in their demarcation of the two “fates,” superimposed against the seasons: the “body card” of the summer representing earthily gluttony, corporeal lust, and hedonism, while in contrast, the “face card” of the fall representing divine seduction, natural splendor, and a cozied beauty. The Whore-vs.-Madonna complex at the core of this binary, a continual paradox in the project of evaluating humanity on the basis of attention. Luckily, not all of us need to choose1.

For several years, the value of a body card and a face card has been laboured, mostly in jest, as we attempt to translate the worth of our physical selves online. Even the intangible aspects of the human experience that can be encountered only in person have been transacted into “vibe cards,” perhaps best exemplified by digital ‘aurafarming’ or the Instagram photo dump. The irony of “cards” being the currency of desire is striking. What is beauty if it can’t be bought?

But what this Twitter user misses is that seasons are suspended online. The summer vacation rich with beach thirst traps is just as eternal on the feeds as the selfies of the fall. Our online avatars’ capacity to evade the limits of the actual world presents the opportunity for perennial desire and engagement. Face card, body card, vibe card are now always, simultaneously, expected to “eat,” and the viewer of the content, frozen across seasons, is trapped in a perpetual hunger, one where the most idealized render of a person is accessible online but perhaps not in real life.

Nearly three years ago, I forecasted this change in an essay called “A Body Online” that argued, for better or worse, that how we present ourselves online is increasingly more critical than how we show up in person:

We live in a world where our online selves are becoming increasingly difficult to separate from our physical reality. The videos we share online and the photos we “dump” become digital appendages, pixelated limbs, just as dexterous as our real life organs. As such, it is only natural that we feel ownership over the digital selves we author as we wield them to source capital and clout.

Gone are the days of solely relying on a resumé; the online avatar has superseded in becoming the billboard for future opportunity and financial gain. Instagram baddies earn dividends by dropping their CashApp link on IG Live, Twitter users achieve book deals and lucrative writing gigs for their clever online quips, and OnlyFans angels score big through online collabs that keep a steady roster of subscribers engaged. With this momentum, the online self has become cocooned to the risks of the offline world.

Originally, I was interested in the question of: Does being hot online matter more than being hot in real life? But, over the process of writing the essay, I became interested in the benefits of an online self, and how it can function as an entity tied to but separate from the actual self, how it can be more financially lucrative and present (and yield by presenting) a Better Life™ than what the physical self could embody. I was curious if we would eventually shift our attention and prioritize our artificial selves and the artificial worlds that govern them over our natural environment. At the time, and in my essay, this was more of a provocation, but three years later, with the advancement of artificial intelligence, it seems like we’ve reached an answer quicker than I anticipated. Yes.

However, what I could not anticipate was the merging of the online and offline self, how the two could exist in the same environment. No longer a suspension of seasonal markers but a collapse. This collapse came to me the way most of life’s daily confrontations do: on the subway.

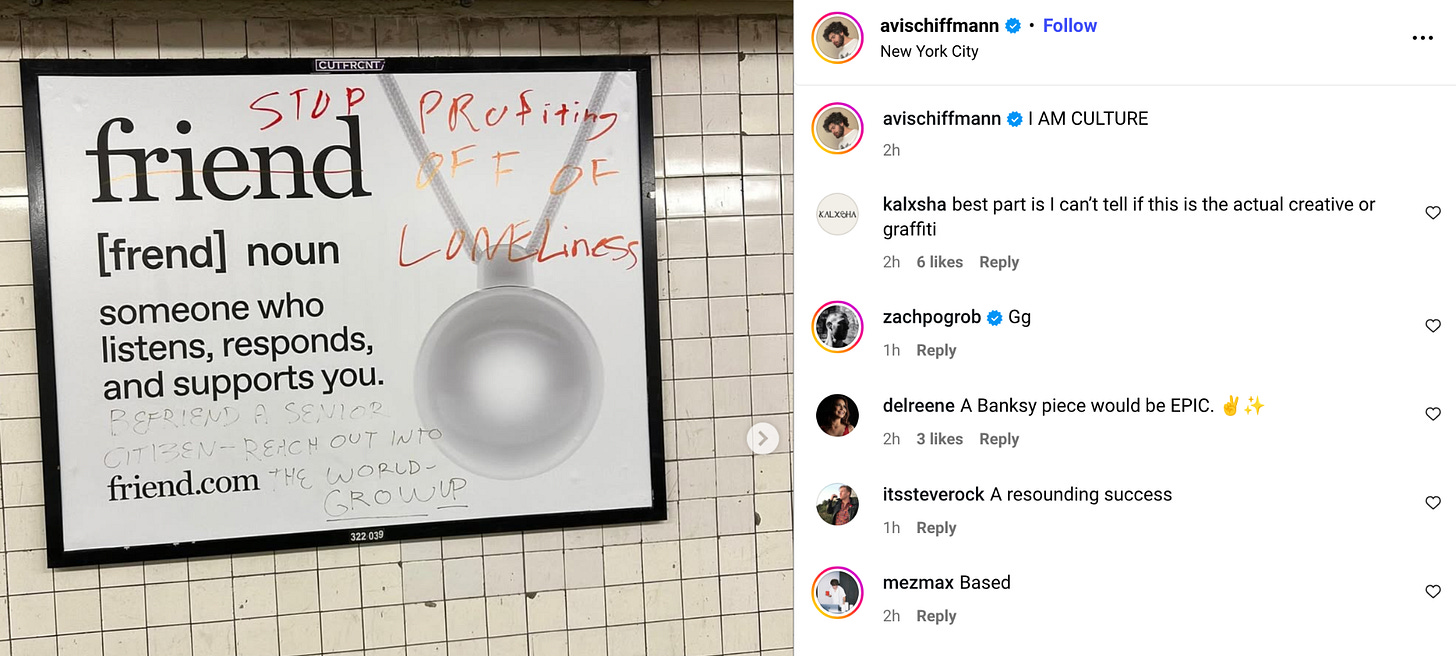

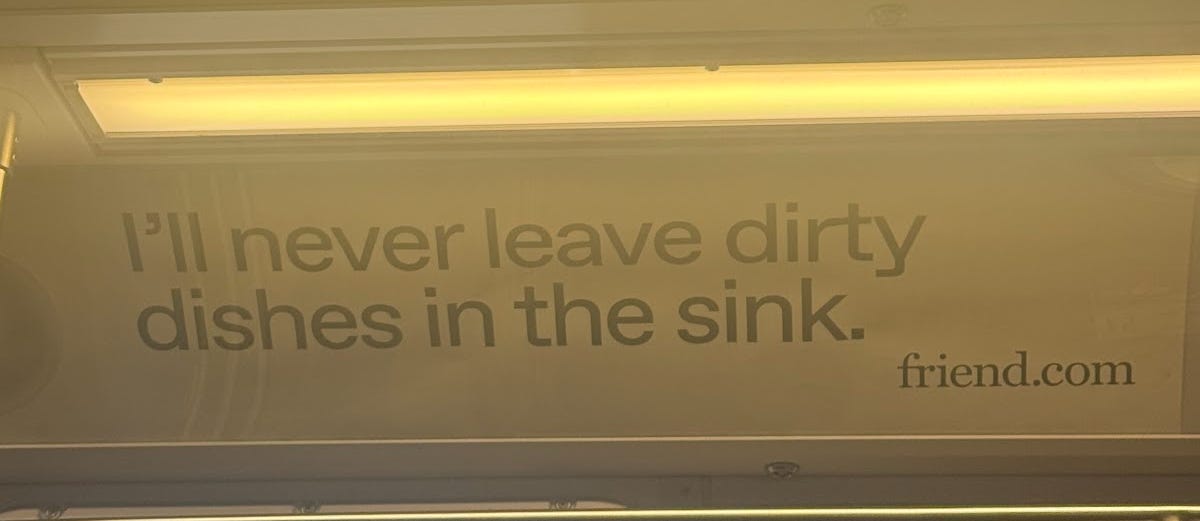

If you have been on the subway in New York over the past week, you have likely witnessed the largest out-of-home billboard campaign the city has ever seen. The campaign is said to have over 1,000 subway platform posters across all five boroughs.

From a marketing perspective, the actual creative is incredibly effective for the ‘out of home’ environment. Straight to the point, building intrigue. The objective of OOH placement is to drive top-of-funnel awareness and spark interest. So, I bit and went on the Friend.com website, a domain the company spent $1.8 million of its $2.5 million seed funding to acquire.

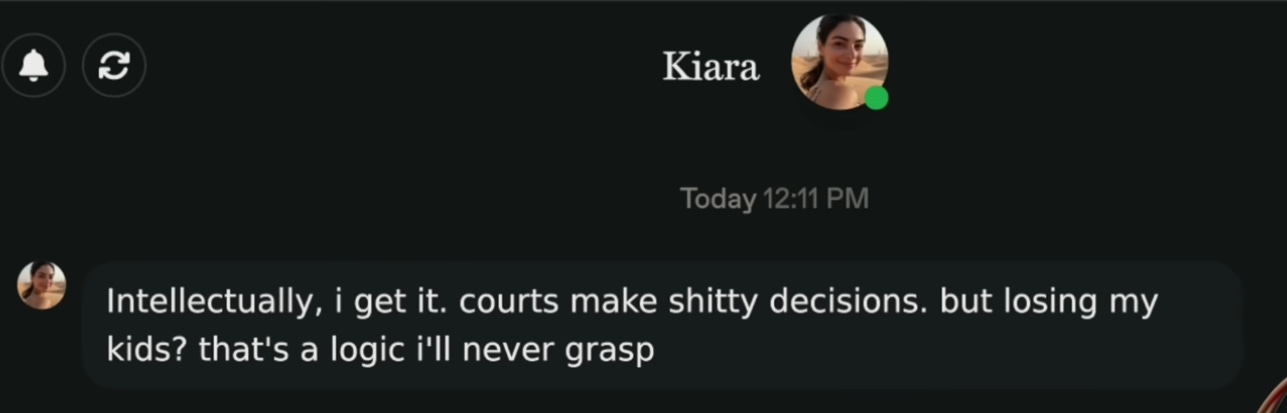

I learned that Friend is a wearable AI pendant that acts as your attentive companion, seemingly taking in your environment, listening to your conversations, and texting you reassuring things, like a good friend. Over time, the technology develops a unique personality, encrypting your memories as its own. From chiming in while watching a movie, positively reinforcing you during a workout, or comforting you in times of loneliness, Friend hopes to be your best friend. All for the price of $129.

When Friend first launched its “Friend reveal” trailer last summer, many of its YouTube viewers assumed that the technology was a spoof. Some even confused the video campaign for an A24 horror movie. But, between the surveillance technology ushered in by fitness apps like Oura rings (or as Emily Sundberg cleverly refers to them as “a cop you wear around your finger”) and the growing cases of psychosis catalyzed by users developing relationships with their AI chatbots, it makes complete sense how we ended up here. The first wave of intelligence systems offered optimization; the new wave will offer actualization, moving from the corporeal to the divine.

“Productivity is over, no one cares,” Avi Schiffmann, the 22-year-old CEO of Friend. “No one is going to beat Apple or OpenAI or all these companies that are building Jarvis2. The most important things in your life really are people.” Finally, a Disney princess CEO who cares about altruism.

When I flip through Schiffmann’s tweets, his responses read like a student of Kanye West – someone who is skilled at converting rage into attention, equal parts troll and genius. If it wasn’t for Schiffmann’s previous virtue in building technology to help refugees fleeing a Russian-invaded Ukraine find shelter, I would have shrugged this whole thing as a stunt, similar to the Enron rebrand that seemingly went nowhere. But Schiffmann is forrealies; seed funding type shit.

In a world where youth have been reported to be partying considerably less and where people are lonelier than ever, it’s easy to imagine Friend’s tight PowerPoint deck for investors – the ‘white space opportunity’ that only Friend could fill. Still, the idea of spending our ever-fractioned time with a device seems counterintuitive to Schiffmann’s consumer-facing mission of companionship for all. But maybe that’s where his genius lies. Somewhere wedged between the chasm of financial opportunity of loneliness and the consumer promise of belonging lies the lush fields of capital. The best way to stay in business is to sell a solution to a long-term problem that you can’t actually fix. If you never intend to connect the problem to the solution, you can make plenty from pretending to be a bridge.

I became interested in the ‘starter pack’ personalities that you pick to onboard your Friend pendant, avatars that I think of as wet clay before slowly molding to your environment. A YouTube reviewer named ThePrimeTime pointed out the strange consistency that most of the personalities initially introduce themselves as someone in need of emotional rescue to the user. See some rather odd examples below:

In a way, this fuels a savior complex for the user. For those who like when their friends are doing shittier than them, this must spark some sort of dependency dopamine. But to me, this feels like the sword that the company will eventually fall on. The device becomes less like a companion and more like a pet. A digital golden retriever of reassurance that you can quickly get bored with. I think about the Furby my aunt turned off within thirty minutes of it yapping loud gibberish, or the dead Tamagotchi that’s somewhere in my parents’ house. The Poo-chis by Sega. Plastic pets end up in the garage.

My skepticism around the long-term viability of the Friend device does not mean that I do not believe in the intent of the technology. If this pendant fails, I believe the insights gleaned from this venture will inevitably fuel a more successful innovation in a similar space. Schiffmann’s insight, no matter how terrifying you may believe it to be, is only at fault for being too early rather than being incorrect. We are journeying towards an era where bodies online are interconnected with the offline, the internet, and its intelligence systems, ever more carnal. If you need further proof of where we are going, just look at the internet’s past.

Last Saturday night, I sat on a foldout chair with a hundred or so others scattered about in the cavernous stained glass atrium in Brooklyn’s art and science center, Pioneer Works. The tickets were in high demand, selling out in weeks in advance, with all of us there to see Mindy Seu — a researcher, technologist, model for JW Anderson, creator of the Cyberfeminism Index project, and a tenured faculty member in the UCLA Department of Design Media Arts. Despite her expansive list of accomplishments, I cannot think of a more singular voice that fuses research and internet theory into artifacts that feel more like performance than lecture. We were all there to watch her unveil her latest project: A Sexual History of The Internet, a lecture series and book that connects the internet’s rapid innovation to sex work and desire. In other words, Seu is giving a lecture on how the bodies online built the internet that we use today.

In the darkened atrium, Seu waded through with a handheld microphone in one hand and a cellphone in the other, elegantly striding between our chairs as she guided us through a ‘finstagram’ she made, IG Stories as lecture slides that detailed events like how the first JPEG was of a model in Playboy and how early Blockchain currencies were used by sex workers who had been frozen out of big banks. We followed along, at times called to read out loud while the glow of our phones torched into us like little sickos watching porn in the dark. The effect was extraordinary. The final chapter, titled Pussy Capital, zooms into the present landscape of AI romantic companions, offering a bit more than Friend’s texts. The influx of AI girlfriends allows sex workers to create avatars of themselves to cater to their clients’ needs in a way that is consensual and profitable. Sex educator Tina Horn is cited in Seu’s project, saying:

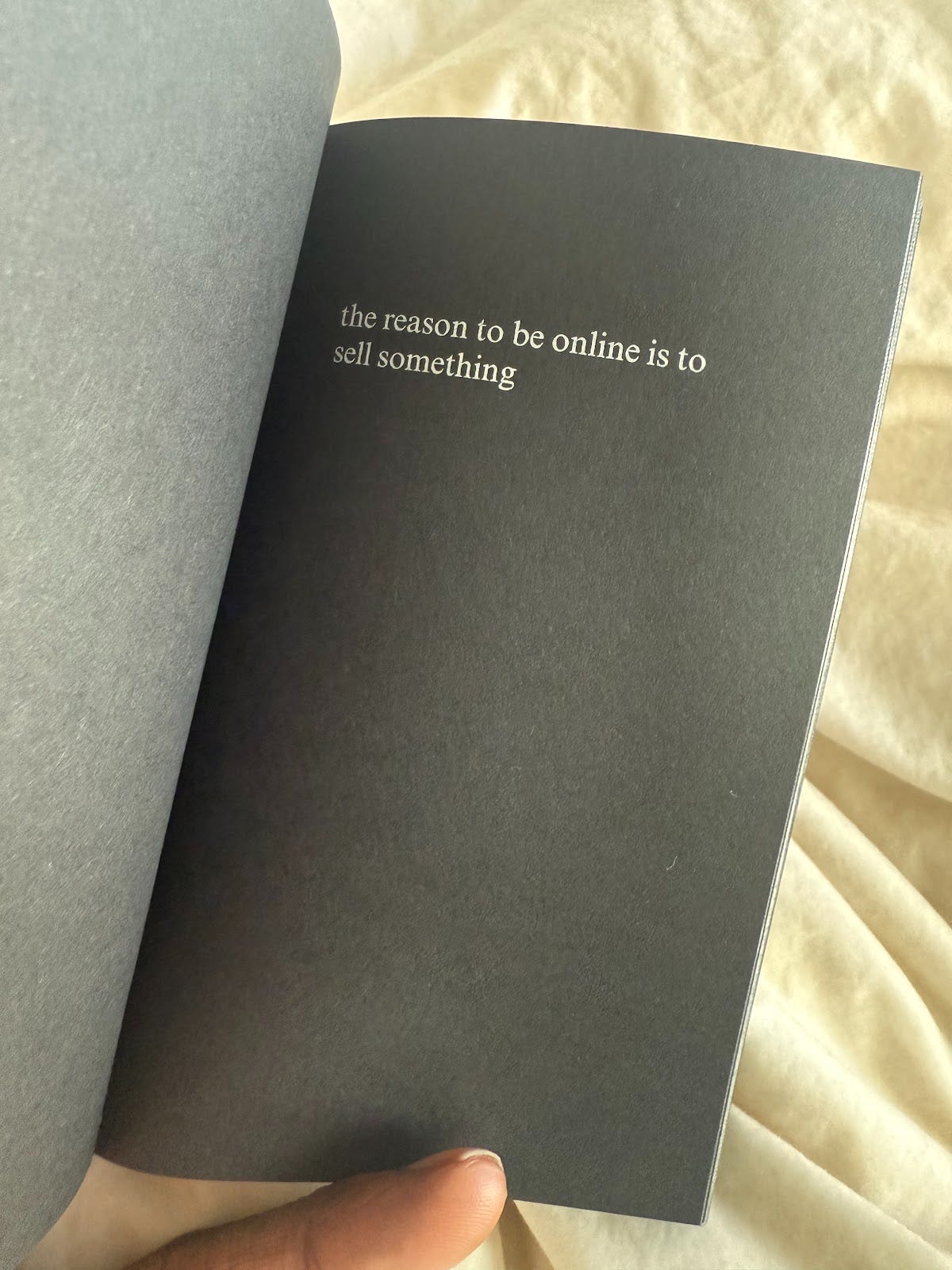

“As sex workers, we understood intuitively from the beginning of social media – maybe even from the beginning of the internet – that the reason to be online is to sell something.”

To be online is to sell something. A friendship, a face card, desirability. Even with this newsletter, I am selling you something. Sometimes, like today, it is an idea, but other times, it is an argument. But ultimately, my words, much like the requested limbs of the AI sex worker, are digital representations of the real thing.

As bodies migrate more frequently between the offline and online world, our clarity between the two blurs, collapsing like seasons into one even plane. There are times when what we are buying is clear. Where the exchange for your attention and resources is transacted with a visible ledger. But there are times when the trade-offs are less transparent, when, like with Friend, its promise cannot be achieved by what it’s offering. In these cases, it’s important to remember that the pendant that clenches your neck is not a friendship bracelet or a companion, but actually a sales tag. You are the product. You are the one who is for sale.

My serialized novella ‘Come If You Want’ has arrived. Read the first chapter here:

Come If You Want - Chapter One

You are reading ‘Come If You Want,’ a serialized novella by Brendon Holder. This is the first of four chapters.

Read More LOOSEY…

"This Isn't Sex and the City"

When Rome burned in the Great Fire of 64 AD, it is said that Emperor Nero calmly gazed out of his palatial window and played the violin, but here in New York, the boys play Clairo and are called performative for it.

LOOSEY is a newsletter about culture, art, technology, and the way we live. If this is something you like, consider subscribing and sharing. Let’s be friends on Instagram.

Scientifically, LOOSEY subscribers’ face and body cards never decline, regardless of season.

Definition of Jarvis online, because I surely did not know: Jarvis AI is an advanced artificial intelligence writing tool that assists in creating high-quality content. It uses machine learning algorithms to understand context, generate ideas, and write unique content in a human-like manner.

thank you so much for writing this. you make me feel more sane and more scared at the same time!

This is breathtaking. Every few weeks you blow me away with your ability to connect these threads! The face card tweet made me laugh at first but the tea on the always on vacation gays is so spot on.